Quantum advantage for NP approximation? For REAL this time?

Saturday, October 5th, 2024The other night I spoke at a quantum computing event and was asked—for the hundredth time? the thousandth?—whether I agreed that the quantum algorithm called QAOA was poised revolutionize industries by finding better solutions to NP-hard optimization problems. I replied that while serious, worthwhile research on that algorithm continues, alas, so far I have yet to see a single piece of evidence that QAOA outperforms the best classical heuristics on any problem that anyone cares about. (Note added: in the comments, Ashley Montanaro shares a paper with empirical evidence that QAOA provides a modest polynomial speedup over known classical heuristics for random k-SAT. This is the best/only such evidence I’ve seen, and which still stands as far as I know!)

I added I was sad to see the arXiv flooded with thousands of relentlessly upbeat QAOA papers that dodge the speedup question by simply never raising it at all. I said that, in my experience, these papers reliably led outsiders to conclude that surely there must be lots of excellent known speedups from QAOA—since otherwise, why would so many people be writing papers about it?

Anyway, the person right after me talked about a “quantum dating app” (!) they were developing.

I figured that, as usual, my words had thudded to the ground with zero impact, truth never having had a chance against what sounds good and what everyone wants to hear.

But then, the morning afterward, someone from the audience emailed me that, incredulous at my words, he went through a bunch of QAOA papers, looking for the evidence of its beating classical algorithms that he knew must be in them, and was shocked to find the evidence missing, just as I had claimed! So he changed his view.

That one message filled me with renewed hope about my ability to inject icy blasts of reality into the quantum algorithms discourse.

So, with that prologue, surely I’m about to give you yet another icy blast of quantum algorithms not helping for optimization problems?

Aha! Inspired by Scott Alexander, this is the part of the post where, having led you one way, I suddenly jerk you the other way. My highest loyalty, you see, is not to any narrative, but only to THE TRUTH.

And the truth is this: this summer, my old friend Stephen Jordan and seven coauthors, from Google and elsewhere, put out a striking preprint about a brand-new quantum algorithm for optimization problems that they call Decoded Quantum Interferometry (DQI). This week Stephen was gracious enough to explain the new algorithm in detail when he visited our group at UT Austin.

DQI can be used for a variety of NP-hard optimization problems, at least in the regime of approximation where they aren’t NP-hard. But a canonical example is what the authors call “Optimal Polynomial Intersection” or OPI, which involves finding a low-degree polynomial that intersects as many subsets as possible from a given list. Here’s the formal definition:

OPI. Given integers n<p with p prime, we’re given as input subsets S1,…,Sp-1 of the finite field Fp. The goal is to find a degree-(n-1) polynomial Q that maximizes the number of y∈{1,…,p-1} such that Q(y)∈Sy, i.e. that intersects as many of the subsets as possible.

For this problem, taking as an example the case p-1=10n and |Sy|=⌊p/2⌋ for all y, Stephen et al. prove that DQI satisfies a 1/2 + (√19)/20 ≈ 0.7179 fraction of the p-1 constraints in polynomial time. By contrast, they say the best classical polynomial-time algorithm they were able to find satisfies an 0.55+o(1) fraction of the constraints.

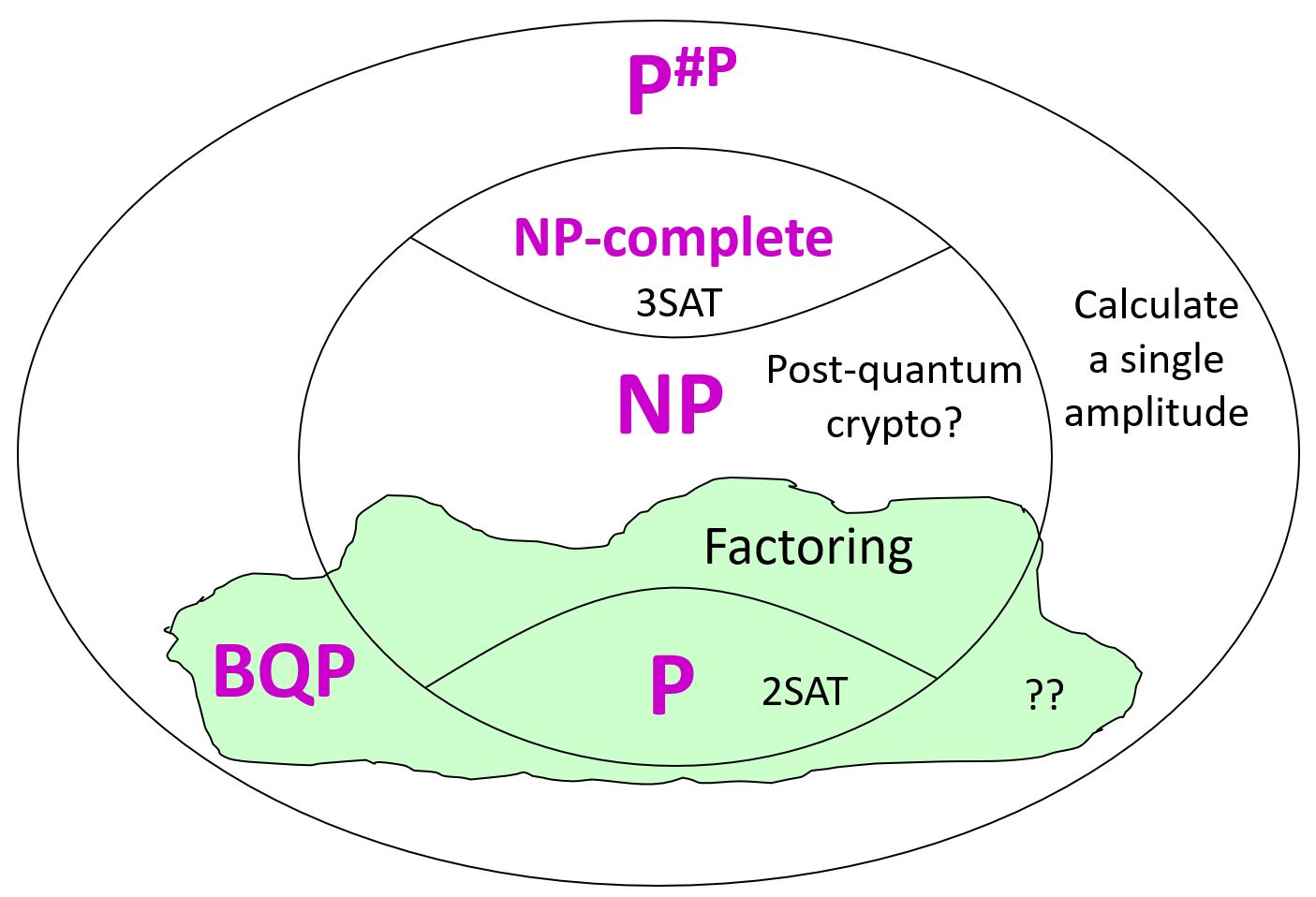

To my knowledge, this is the first serious claim to get a better approximation ratio quantumly for an NP-hard problem, since Farhi et al. made the claim for QAOA solving something called MAX-E3LIN2 back in 2014, and then my blogging about it led to a group of ten computer scientists finding a classical algorithm that got an even better approximation.

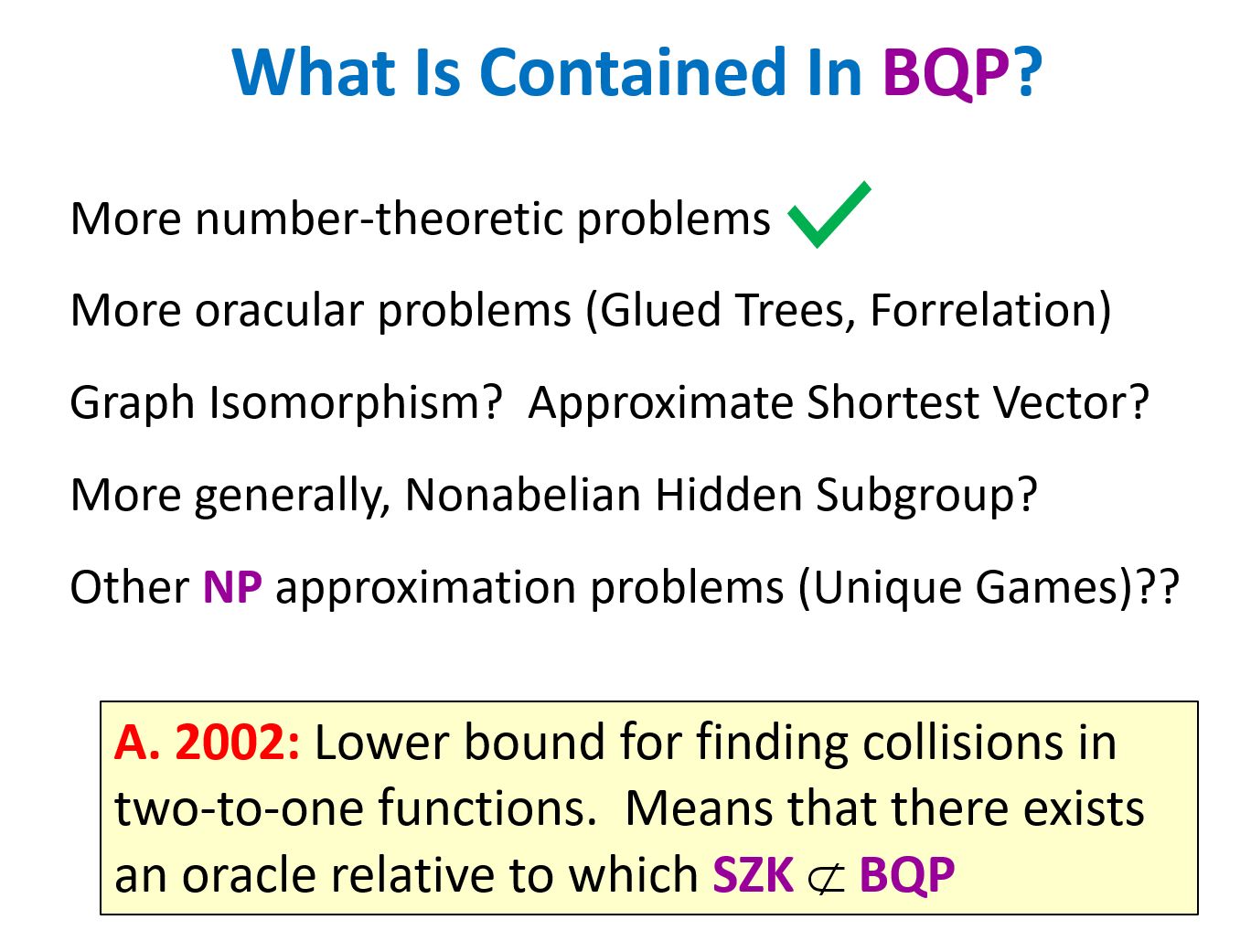

So, how did Stephen et al. pull this off? How did they get around the fact that, again and again, exponential quantum speedups only seem to exist for algebraically structured problems like factoring or discrete log, and not for problems like 3SAT or Max-Cut that lack algebraic structure?

Here’s the key: they didn’t. Instead they leaned into the fact, by targeting an optimization problem that (despite being NP-hard) has loads of algebraic structure! The key insight, in their new DQI algorithm, is that the Quantum Fourier Transform can be used to reduce other NP-hard problems to problems of optimal decoding of a suitable error-correcting code. (This insight built on the breakthrough two years ago by Yamakawa and Zhandry, giving a quantum algorithm that gets an exponential speedup for an NP search problem relative to a random oracle.)

Now, sometimes the reduction to a coding theory problem is “out of the frying pan and into the fire,” as the new optimization problem is no easier than the original one. In the special case of searching for a low-degree polynomial, however, the optimal decoding problem ends up being for the Reed-Solomon code, where we’ve known efficient classical algorithms for generations, famously including the Berlekamp-Welch algorithm.

One open problem that I find extremely interesting is whether OPI, in the regime where DQI works, is in coNP or coAM, or has some other identifiable structural feature that presumably precludes its being NP-hard.

Regardless, though, as of this week, the hope of using quantum computers to get better approximation ratios for NP-hard optimization problems is back in business! Will that remain so? Or will my blogging about such an attempt yet again lead to its dequantization? Either way I’m happy.

Follow

Follow