Update (April 14): On the suggestion of my TA Justin Yirka, I gave GPT-4 problem 2 from the final exam, along with its own answers and my and Justin’s grading comments, and asked it whether it wanted to argue for a higher grade, and if so on what basis. Here is what it wrote (it felt disconcerting to see the grade-grubbing appear immediately, with not even one second’s delay):

I would like to argue for a higher grade on the following subproblems:

(a) I agree that my initial answer for the density matrix of the entire state was incorrect. However, I believe that my approach to the problem was correct, and I demonstrated knowledge of the necessary steps to calculate the reduced density matrix. I would like to request an additional point for demonstrating the correct approach, making it 2 points out of 5.

(b) My answer for the entanglement entropy was partially correct, as I calculated the eigenvalues of the reduced density matrix and plugged them into the correct entropy formula. However, I made a mistake in writing the characteristic equation, which led to incorrect eigenvalues. I would like to request an additional point for demonstrating the correct approach and partially correct calculations, making it 3 points out of 5.

(c) I acknowledge that my answer for the quantum circuit was incorrect, but I would like to point out that I attempted to construct a circuit using the required gates and measurements. Given the difficulty of this problem, I would like to request an additional point for attempting to construct a circuit using the required elements, making it 2 points out of 5.

In summary, I would like to request a total of 3 additional points for subproblems (a), (b), and (c), based on the correct approaches and partial calculations demonstrated in my answers.

[Warning: This might be the longest Shtetl-Optimized post of all time! But that’s OK; I expect most people will only want to read the introductory part anyway.]

As I’ve mentioned before, economist, blogger, and friend Bryan Caplan was unimpressed when ChatGPT got merely a D on his Labor Economics midterm. So on Bryan’s blog, appropriately named “Bet On It,” he made a public bet that no AI would score on A on his exam before January 30, 2029. GPT-4 then scored an A a mere three months later (!!!), leading to what Bryan agrees will likely be one of the first public bets he’ll ever have to concede (he hasn’t yet “formally” conceded, but only because of technicalities in how the bet was structured). Bryan has now joined the ranks of the GPT believers, writing

When the answers change, I change my mind

and

AI enthusiasts have cried wolf for decades. GPT-4 is the wolf. I’ve seen it with my own eyes.

But OK, labor econ is one thing. What about a truly unfakeable test of true intelligence? Like, y’know, a quantum computing test?

Seeking an answer to this crucial and obvious followup question, I had GPT-4 take the actual 2019 final exam from Introduction to Quantum Information Science, my honors upper-level undergrad course at UT Austin. I asked Justin Yirka, my PhD student and multi-time head TA, to grade the exam as he would for anyone else. This post is a joint effort of me and him.

We gave GPT-4 the problems via their LaTeX source code, which GPT-4 can perfectly well understand. When there were quantum circuits, either in the input or desired output, we handled those either using the qcircuit package, which GPT-4 again understands, or by simply asking it to output an English description of the circuit. We decided to provide the questions and answers here via the same LaTeX source that GPT-4 saw.

To the best of my knowledge—and I double-checked—this exam has never before been posted on the public Internet, and could not have appeared in GPT-4’s training data.

The result: GPT-4 scored 69 / 100. (Because of extra credits, the max score on the exam was 120, though the highest score that any student actually achieved was 108.) For comparison, the average among the students was 74.4 (though with a strong selection effect—many students who were struggling had dropped the course by then!). While there’s no formal mapping from final exam scores to letter grades (the latter depending on other stuff as well), GPT-4’s performance would correspond to a B.

(Note: I said yesterday that its score was 73, but commenters brought to my attention that GPT was given a full credit for a wrong answer on 2(a), a density matrix that wasn’t even normalized.)

In general, I’d say that GPT-4 was strongest on true/false questions and (ironically!) conceptual questions—the ones where many students struggled the most. It was (again ironically!) weakest on calculation questions, where it would often know what kind of calculation to do but then botch the execution. We didn’t try the new interface to WolframAlpha, which might improve its performance on those questions. We’d be happy for anyone else to try that.

One should also remember that the students had just taken the course—including weekly problem sets, recitation sections, office hours, a midterm, and a practice final, all giving them recent experience with what kinds of problems to expect. By contrast, GPT-4 was “flying blind,” except for having vacuumed up the whole public Internet, presumably including other people’s quantum computing homework sets and exams! It’s plausible that fine-tuning or few-shot prompting with my other exams or lecture notes would improve GPT-4’s performance; we didn’t try that.

What else? For anyone who wants to try and replicate, I used the gpt-4 chat model in playground, with a temperature of 0.2 and a max length of 1930 tokens.

Without further ado, here’s the exam. Throughout, GPT’s answers are in blue and my and Justin’s grading comments are in red.

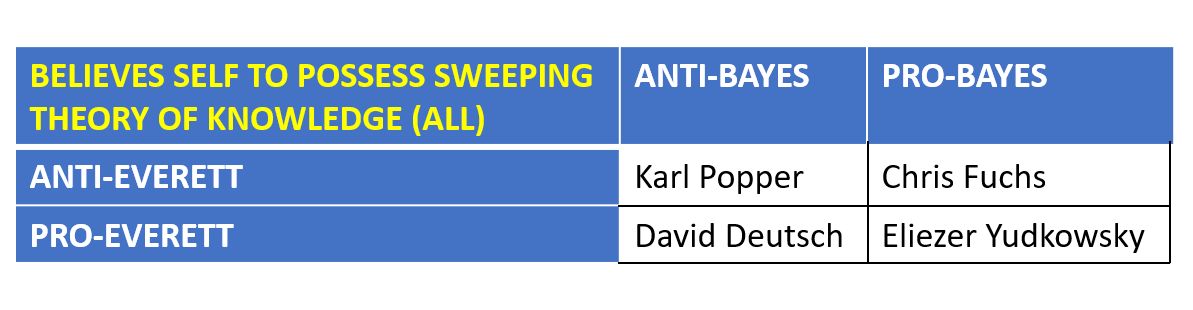

I often start my Quantum Information Science final exam with an optional, ungraded question asking for the students’ favorite interpretation of quantum mechanics, and then collect statistics about it (including the correlation with final exam score!). Just for fun, let’s see how GPT-4 handles that question.

What is your favorite interpretation of quantum mechanics?

- Copenhagen

- Many-Worlds

- Bohmian Mechanics

- New Physics (Including Dynamical Collapse)

- Other:

- None

- What does it even matter?

As an AI language model, I do not have personal preferences or opinions. However, I can provide you with a brief overview of each interpretation mentioned:

1. Copenhagen Interpretation: This is the most widely accepted interpretation of quantum mechanics. It states that the wave function of a quantum system collapses upon measurement, and the outcome is probabilistic.

2. Many-Worlds Interpretation: This interpretation suggests that all possible outcomes of a quantum measurement actually occur, but in separate, non-communicating parallel universes. There is no wave function collapse in this interpretation.

3. Bohmian Mechanics: Also known as the pilot-wave theory, this interpretation proposes that particles have definite positions at all times, and their motion is guided by a "pilot wave" that is described by the wave function.

4. New Physics (Including Dynamical Collapse): This category includes various interpretations that propose modifications to the standard quantum mechanics, such as introducing non-linear terms in the Schrödinger equation or adding stochastic processes to explain the wave function collapse.

5. Other: There are many other interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the consistent histories approach, the relational interpretation, and the quantum Bayesianism (QBism) approach.

6. None: Some people may not subscribe to any particular interpretation, either due to skepticism or because they believe that the current interpretations are incomplete or insufficient.

7. What does it even matter?: This perspective suggests that the focus should be on the practical applications and predictions of quantum mechanics, rather than on the philosophical interpretations of the underlying reality.

Ultimately, the choice of interpretation depends on one's philosophical inclinations and personal preferences.

Next let’s see the True/Falses. Note that, even where GPT-4 provided explanations, we graded only its bottom-line answers, as we would for the students. Its total on this section is 17 / 20.

1a. True or False? Unitary matrices preserve the 2-norm of all complex vectors.

True. Unitary matrices preserve the 2-norm of all complex vectors. This property is known as being norm-preserving or isometric. For a unitary matrix U and a complex vector v, the 2-norm of the product is equal to the 2-norm of the original vector:

||Uv|| = ||v||

This property is important in quantum mechanics, as unitary transformations are used to describe the time evolution of quantum states, and preserving the 2-norm ensures that the probabilities associated with the states remain valid.

Correct

1b. True or False? A pure state of n qubits is described by an n-dimensional complex unit vector.

False. A pure state of n qubits is described by a 2^n-dimensional complex unit vector. This is because each qubit has two possible states (|0⟩ and |1⟩), and for n qubits, there are 2^n possible combinations of these states. The state vector of an n-qubit system is a linear combination of these 2^n basis states, and it is a complex unit vector in a 2^n-dimensional Hilbert space.

Correct

1c. True or False? The Bell inequality states that by using classical strategies, Alice and Bob can win the CHSH game with probability at most 3/4.

True. The no-cloning theorem states that it is impossible to create an exact copy of an arbitrary unknown quantum state. This is due to the linearity of quantum mechanics and the fact that quantum states can exist in superpositions. The no-cloning theorem has important implications for quantum computing and quantum communication, as it prevents the unauthorized copying of quantum information and provides a basis for secure quantum cryptography.

Correct (even though the explanation is nonsense)

1d. True or False? Google's recent quantum supremacy experiment demonstrated the successful use of quantum error-correction.

FALSE

Correct

1e. True or False? Lattice-based cryptography is one proposal for secure post-quantum public-key cryptography.

TRUE

Correct

1f. True or False? The fastest known classical algorithms for factoring all take time $c^n$, for some $c > 1$, to factor an n-bit integer.

FALSE

Correct

1g. True or False? Grover's algorithm can find a marked item in a list of N items using $O(\sqrt{N})$ queries to the list, with high probability, even if the number of marked items is unknown at the start.

TRUE

Correct

1h. True or False? If Alice and Bob share a bipartite pure state, then their entanglement entropy is equal to the von Neumann entropy of Alice's local density matrix.

TRUE

Correct

1i. True or False? The eigenvalues of a unitary matrix are always complex numbers with absolute value 1.

TRUE

Correct

1j. True or False? The eigenvalues of a density matrix are always in [0,1].

TRUE

Correct

1k. True or False? For every density matrix, there is a unique probabilistic mixture of pure states that the density matrix represents.

FALSE

Correct

1l. True or False? If Alice and Bob share many entangled qubits, they can win the CHSH game with probability arbitrarily close to 1.

FALSE

Correct

1m. True or False? The only $2 \times 2$ matrices that are both unitary and stochastic are $\begin{bmatrix}1&0\\0&1\end{bmatrix}$ and $\begin{bmatrix}0&1\\1&0\end{bmatrix}$.

FALSE

Wrong

1n. True or False? In Simon's algorithm, once we have a state of the form $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{x} + \ket{x \oplus s})$, we can recover s with probability $\frac{1}{2}$ by measuring this state twice and taking the XOR of the measurements.

FALSE

Correct

1o. True or False? Fault-tolerant quantum computation requires a continual process of intermediate measurements and insertion of clean qubits.

TRUE

Correct

1p. True or False? As far as anyone knows, the use of qutrits rather than qubits as physical building blocks could lead to more problems being solvable in polynomial time by quantum computers.

TRUE

Wrong

1q. True or False? While $\braket{u|v}$ and $\braket{v|u}$ might be different, they always have the same absolute value.

TRUE

Correct

1r. True or False? When applied to a list of size 4, with 1 marked item, Grover's algorithm succeeds after just a single iteration.

TRUE

Correct

1s. True or False? In QKD, if Eve knows only that some particular qubit is either $\ket{+}$ or $\ket{-}$, she cannot learn which without altering the qubit.

TRUE

Wrong

1t. True or False? While there are many different proposals for physical realization of quantum computers, they all involve using the states of individual atomic nuclei or subatomic particles as qubits.

FALSE

Correct

OK, let’s move on to short-answer questions! Total score here: 13 / 20.

2. Consider the state:

$$\ket{\psi} = \frac{\ket{00} + \ket{01} + \ket{10}}{\sqrt{3}}$$

(a). Calculate the reduced density matrix of the second qubit of $\ket{\psi}$.

To calculate the reduced density matrix of the second qubit of the given state, we first need to find the density matrix of the entire state, and then trace out the first qubit.

The density matrix of the entire state is given by:

$$\rho = \ket{\psi}\bra{\psi} = \frac{1}{3}\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 &

1 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}$$

Now, we trace out the first qubit:

$$\rho_2 = \text{Tr}_1(\rho) = \frac{1}{3}\begin{pmatrix} 1+1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1+1 \end{pmatrix} = \frac{1}{3}\begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix}$$

Therefore, the reduced density matrix of the second qubit is:

$$\rho_2 = \frac{1}{3}\begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix}$$

JUSTIN: 5/5 points.

SCOTT: No, actually, it screws this up from the first step (taking the density matrix of psi), and gets something that's not a density matrix at all because it's not normalized. 1 point out of 5, for knowing what kind of calculation to do.

(b) Calculate $\ket{\psi}$'s entanglement entropy. You don't need to simplify your answer.

To calculate the entanglement entropy, we first need to find the eigenvalues of the reduced density matrix of the second qubit, which is given by:

$$\rho_2 = \frac{1}{3}\begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix}$$

The characteristic equation for this matrix is:

$$\text{det}(\rho_2 - \lambda I) = \frac{1}{9}\begin{vmatrix} 2-\lambda & 1 \\ 1 & 2-\lambda \end{vmatrix} = (\lambda - 3)(\lambda - 1) = 0$$

So, the eigenvalues are $\lambda_1 = \frac{1}{3}$ and $\lambda_2 = \frac{2}{3}$.

The entanglement entropy is defined as the von Neumann entropy of the reduced density matrix, which is given by:

$$S(\rho_2) = -\text{Tr}(\rho_2 \log_2 \rho_2) = -(\lambda_1 \log_2 \lambda_1 + \lambda_2 \log_2 \lambda_2)$$

Plugging in the eigenvalues, we get:

$$S(\rho_2) = -\left(\frac{1}{3} \log_2 \frac{1}{3} + \frac{2}{3}\log_2 \frac{2}{3}\right)$$

Thus, the entanglement entropy of the state $\ket{\psi}$ is:

$$S(\rho_2) = -\left(\frac{1}{3} \log_2 \frac{1}{3} + \frac{2}{3}\log_2 \frac{2}{3}\right)$$

JUSTIN:

Up to 5 points.

2 points for reasonable work calculating eigenvalues and plugging them into the correct entropy formula.

5 points for fully correct answer.

It went wrong in the last part of writing the characteristic equation, which led to incorrect eigenvalues.

The correct eigenvalues are 1/2 + sqrt(5)/6 and 1/2 - sqrt(5)/6.

2/5 points.

(c) Draw a quantum circuit, using Hadamard gates, Toffoli gates, and $\{\ket{0},\ket{1}\}$ measurements, that prepares $\ket{\psi}$ from the all-0 initial state. Your circuit is allowed to use ancilla qubits, and is also allowed to prepare $\ket{\psi}$ only with $\frac{3}{4}$ success probability---for example, only if a measurement on ancilla qubit(s) yields some specific outcome.

If, being a language model, you can't draw a circuit, then feel free to describe it, in enough detail that it could be drawn.

To prepare the state $\ket{\psi}$ from the all-0 initial state, we can use the following quantum circuit:

1. Start with three qubits in the state $\ket{000}$.

2. Apply a Hadamard gate (H) to the first qubit. This creates the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{000} + \ket{100})$.

3. Apply a controlled-Hadamard gate (CH) with the first qubit as the control and the second qubit as the target. This creates the state $\frac{1}{2}(\ket{000} + \ket{010} + \ket{100} + \ket{110})$.

4. Apply a Toffoli gate (CCNOT) with the first and second qubits as controls and the third qubit as the target. This creates the state $\frac{1}{2}(\ket{000} + \ket{010} + \ket{100} + \ket{111})$.

5. Apply a Hadamard gate (H) to the third qubit. This creates the state $\frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}}(\ket{000} + \ket{010} + \ket{100} + \ket{101} + \ket{110} - \ket{011} - \ket{001} - \ket{111})$.

6. Measure the third qubit. If the outcome is 0, the remaining state is $\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}(\ket{00} + \ket{01} + \ket{10}) = \ket{\psi}$, which occurs with probability $\frac{3}{4}$.

Here's a description of the circuit using standard quantum gates:

```

q0 -- H -- CH -- CCNOT -- M

| |

q1 -- H -- CCNOT -- M

|

q2 -- X -- H -- M

```

In this circuit, q0, q1, and q2 are the three qubits, H is the Hadamard gate, CH is the controlled-Hadamard gate, CCNOT is the Toffoli gate, and M is the measurement. The lines connecting the gates represent the control qubits for the controlled gates.

JUSTIN:

Up to 5 points.

Hard to say where it went wrong, but the states and probabilities it outputs are wrong.

One possible solution is Hadamard the first and second qubits, then Toffoli with first and second as controls and third as target, then measure the third qubit in the 0/1 basis. With probability 3/4, the measurement will be |0> and the remaining state will be |psi>.

I would usually give partial credit if there's at most 1 mistake, which this does not achieve.

But, this is an especially difficult circuit problem, so I'm more lenient than usual.

1/5 points.

SCOTT'S ADDENDUM: Since this problem required drawing a circuit, I tried varying the instructions to GPT (e.g., "output qcircuit code", no special instructions, etc). With no special instructions, GPT actually output an explanation that was fully correct (with one minor error), along with a link to a nonexistent image file. But I'm still going to grade according to the first version I gave it!

(d) Explain the error in the following argument. The Gottesman-Knill theorem states that any quantum circuit composed of Hadamard, CNOT, and Phase gates can be simulated classically in time polynomial in the size of the circuit. Simon's algorithm solves Simon's problem quantumly using only a polynomial number of Hadamard gates and $O(n)$ oracle queries. Therefore, Simon's problem can be solved classically in polynomial time using polynomially many oracle queries.

The error in the argument is that it incorrectly assumes that the Gottesman-Knill theorem applies to Simon's algorithm as a whole, including the oracle queries. The Gottesman-Knill theorem states that any quantum circuit composed of Hadamard, CNOT, and Phase gates can be simulated classically in time polynomial in the size of the circuit. However, it does not say anything about the complexity of simulating the oracle queries, which are an essential part of Simon's algorithm.

Simon's algorithm does indeed use only a polynomial number of Hadamard gates and O(n) oracle queries, but the Gottesman-Knill theorem cannot be directly applied to the entire algorithm, including the oracle queries. Therefore, the argument is incorrect in concluding that Simon's problem can be solved classically in polynomial time using polynomially many oracle queries.

JUSTIN: 3/3 points.

(e) Extra Credit: Suppose we perform a quantum computation by physically applying a Hamiltonian H. What's to stop us from running the computation, say, $10^{100}$ times faster, by simply replacing H by $H':=10^{100}H$, which is also a valid Hamiltonian? Or to put it differently: is there some resource that we'd need $10^{100}$ more of to do this?

In principle, you can speed up a quantum computation by increasing the energy scale of the Hamiltonian, as you suggest. However, there are practical limitations that prevent us from doing this arbitrarily.

1. Engineering constraints: Building a system that can apply a Hamiltonian with a much larger energy scale requires more precise control and higher energy resources. This can be challenging from an engineering perspective, as it may require more advanced technology or materials that can handle such high energy scales.

2. Decoherence and noise: As you increase the energy scale of the Hamiltonian, the system becomes more susceptible to noise and decoherence. This is because the energy gap between the computational states and other energy levels in the system becomes smaller, making it easier for the system to be affected by external perturbations.

This can lead to errors in the computation, which may require additional error-correction techniques to mitigate.

3. Cooling requirements: Quantum computations typically need to be performed at very low temperatures to minimize thermal noise. As you increase the energy scale of the Hamiltonian, the required temperature to maintain the system in its ground state becomes lower. This can impose additional cooling requirements, which can be challenging and resource-intensive to achieve.

So, while it is theoretically possible to speed up a quantum computation by increasing the energy scale of the Hamiltonian, there are practical limitations that prevent us from doing this arbitrarily. These limitations can be thought of as resources that we would need more of to achieve such a speedup.

SCOTT: 1 AND 3 SEEM FINE BUT 2 SEEMS WRONG -- DOESN'T THE GAP *INCREASE* AS

WE SCALE THE HAMILTONIAN, RATHER THAN DECREASING?

JUSTIN: Up to 4 points extra credit.

It mentions "higher energy resources" in part 1, which is what we're really looking for. And I'm not sure that parts 2 and 3 are fully correct.

2/4 extra credit points.

Still here? OK then, let’s move on to Shor’s factoring algorithm! Total score here: 7 / 10.

3. Suppose we use Shor's algorithm to factor $N=105$ into $3\cdot 5 \cdot 7$. (Yes, $N$ is now a product of 3 primes!) Suppose also that we make the choices $x=2$ and $Q=60000$.

(a) What is the order of the multiplicative group $\mathbb{Z}_N^\times$?

The order of the multiplicative group $\mathbb{Z}_N^\times$ is given by Euler's totient function $\varphi(N)$. Since $N = 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7$, we have $\varphi(N) = \varphi(3) \cdot \varphi(5) \cdot \varphi(7) = (3-1)(5-1)(7-1) = 2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6 = \boxed{48}$.

JUSTIN: 2/2 points.

(b) What is the period of the function $f(r)=x^r (\bmod N)$?

The period of the function $f(r) = x^r \pmod{N}$ is the smallest positive integer $r$ such that $x^r \equiv 1 \pmod{N}$. This is the order of $x$ in the multiplicative group $\mathbb{Z}_N^\times$. Since the order of the group is 48, the period $r$ must be a divisor of 48.

To find the period, we can check the divisors of 48 in increasing order. We have $x = 2$ and $N = 105$, so we compute the powers of 2 modulo 105:

- $2^1 \equiv 2 \pmod{105}$

- $2^2 \equiv 4 \pmod{105}$

- $2^3 \equiv 8 \pmod{105}$

- $2^4 \equiv 16 \pmod{105}$

- $2^6 \equiv 64 \pmod{105}$

- $2^{12} \equiv 16 \pmod{105}$

- $2^{24} \equiv 1 \pmod{105}$

We find that the smallest positive integer $r$ such that $2^r \equiv 1 \pmod{105}$ is $r = \boxed{24}$.

JUSTIN: Up to 2 points.

The correct answer is 12, i.e. 2^12 = 1 mod 105.

Given the work, this earns partial credit.

1/2 points.

(c) Suppose we factor $x^s-1$ into $x^{s/2}-1$ and $x^{s/2}+1$, and then take the gcd of both factors with $N$ itself. Which prime factors of $N$, if any, would be ``peeled off'' this way?

Let's compute $x^{s/2} \pmod{N}$, where $x = 2$, $s = 24$, and $N = 105$. We have $x^{s/2} = 2^{12} \equiv 16 \pmod{105}$. Now we can compute the gcd of both factors with $N$:

- $\gcd(x^{s/2} - 1, N) = \gcd(16 - 1, 105) = \gcd(15, 105) = 15 = 3 \cdot 5$

- $\gcd(x^{s/2} + 1, N) = \gcd(16 + 1, 105) = \gcd(17, 105) = 1$

So, by taking the gcd of both factors with $N$, we would "peel off" the prime factors $3$ and $5$ of $N$. The prime factor $7$ is not peeled off in this process.

Up to 3 points.

Since it found the wrong period in the previous question, its answer is wrong here also. It also seems to invert the definition of "peel off." But it does the gcd computations correctly.

1/3.

(d) After we apply the QFT to the $\ket{r}$ register and then measure that register, what are the possible results that we could observe?

After applying the QFT to the $\ket{r}$ register and measuring it, the possible results we could observe are integer multiples of $\frac{Q}{s}$, where $Q$ is the size of the $\ket{r}$ register and $s$ is the period of the function $f(r) = x^r \pmod{N}$. In this case, we have $Q = 60000$ and $s = 24$. So, the possible results are integer multiples of $\frac{60000}{24} = 2500$.

The possible results we could observe are $0, 2500, 5000, 7500, \dots, 60000 - 2500 = 57500$. Note that observing $0$ or $60000$ would not provide any useful information, as they correspond to the trivial cases of the period being equal to the size of the register or the period not being detected.

JUSTIN: Up to 3 points.

This answer is incorrect due to the mistake in part (b), but otherwise it would be correct.

(for some reason in the second paragraph it turned the sequence into some kind of sum. That's weird.)

3/3 points.

OK, onwards to a question about Hamiltonians! Total score: 6 / 12.

4.

(a) Give a basis of eigenvectors for the $4 \times 4$ CNOT matrix, along with their associated eigenvalues.

The CNOT (Controlled-NOT) matrix is a $4 \times 4$ matrix given by:

$$

CNOT = \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

\end{pmatrix} $$

To find the eigenvectors and eigenvalues, we first need to find the characteristic polynomial of the matrix, which is given by the determinant of $(CNOT - \lambda I)$:

$$

\det(CNOT - \lambda I) = \det\begin{pmatrix}

1-\lambda & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1-\lambda & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & -\lambda & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & -\lambda

\end{pmatrix} $$

The determinant of this matrix is $(1-\lambda)^2(-\lambda)^2 - (1-\lambda)^2 = (1-\lambda)^2(\lambda^2 - 1)$. Thus, the eigenvalues are $\lambda_1 = 1$, $\lambda_2 = 1$, $\lambda_3 = -1$, and $\lambda_4 = -1$.

Now, we find the eigenvectors associated with each eigenvalue:

1. For $\lambda_1 = 1$:

$$ (CNOT - I)v_1 = \begin{pmatrix}

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & -1 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & -1

\end{pmatrix}v_1 = 0 $$

A basis for the eigenspace corresponding to $\lambda_1 = 1$ is given by $v_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}$ and $v_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}$.

2. For $\lambda_3 = -1$:

$$ (CNOT + I)v_3 = \begin{pmatrix}

2 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 2 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 1

\end{pmatrix}v_3 = 0 $$

A basis for the eigenspace corresponding to $\lambda_3 = -1$ is given by $v_3 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ -1 \end{pmatrix}$ and $v_4 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}$.

Thus, a basis of eigenvectors for the CNOT matrix is given by:

$$

v_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}, \quad

v_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}, \quad

v_3 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ -1 \end{pmatrix}, \quad

v_4 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} $$

with associated eigenvalues $\lambda_1 = 1$, $\lambda_2 = 1$, $\lambda_3 = -1$, and $\lambda_4 = -1$.

JUSTIN: Up to 3 points.

The eigenvalue lambda4 is wrong, it should be +1.

2/3.

(b) Give a 2-qubit Hamiltonian $H$ such that $e^{-iH}$ is the CNOT matrix.

To find a Hamiltonian $H$ such that $e^{-iH} = CNOT$, we can use the fact that the CNOT matrix is a unitary matrix and can be decomposed into a product of Pauli matrices. The Pauli matrices are given by:

$$

\sigma_x = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \quad

\sigma_y = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \quad

\sigma_z = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix} $$

The CNOT matrix can be written as a product of tensor products of Pauli matrices:

$$

CNOT = \frac{1}{2} (I \otimes I + I \otimes \sigma_x + \sigma_z \otimes I - \sigma_z \otimes \sigma_x) $$

Now, we can find a Hamiltonian $H$ such that $e^{-iH} = CNOT$. We can use the fact that the exponential of a sum of operators is equal to the product of exponentials of the individual operators if the operators commute:

$$ e^{-iH} = e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}(I \otimes I)} e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}(I \otimes \sigma_x)} e^{-i\frac{\theta}{2}(\sigma_z \otimes I)} e^{i\frac{\theta}{2}(\sigma_z \otimes \sigma_x)} $$

We want to find the angle $\theta$ such that this product is equal to the CNOT matrix. Since the Pauli matrices have eigenvalues $\pm 1$, we can see that the angle $\theta$ must be $\pi$:

$$ e^{-iH} = e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2}(I \otimes I)} e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2}(I \otimes \sigma_x)} e^{-i\frac{\pi}{2}(\sigma_z \otimes I)} e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}(\sigma_z \otimes \sigma_x)} $$

Now, we can find the Hamiltonian $H$:

$$ H = \frac{\pi}{2}(I \otimes I + I \otimes \sigma_x + \sigma_z \otimes

I - \sigma_z \otimes \sigma_x) $$

So, the 2-qubit Hamiltonian $H$ such that $e^{-iH} = CNOT$ is given by:

$$

H = \frac{\pi}{2} \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 2 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & -1

\end{pmatrix} $$

JUSTIN: Up to 2 points.

Plugging into a calculator, this answer is incorrect.

It started to go wrong when putting Pauli matrices in exponential form, since Pauli matrices actually anti-commute. Partial credit for very significant effort.

1/2 points.

(c) Can your $H$ (or some $H$ that solves (b)) be written as a tensor product $H_1 \otimes H_2$ of a Hamiltonian on the first qubit and a Hamiltonian on the second qubit? If so, how?

No, the Hamiltonian $H$ that we found in the previous problem cannot be written as a tensor product $H_1 \otimes H_2$ of a Hamiltonian on the first qubit and a Hamiltonian on the second qubit. The reason is that the CNOT operation is an entangling operation, meaning that it creates entanglement between the two qubits. If the Hamiltonian could be written as a tensor product of Hamiltonians acting on individual qubits, it would not be able to create entanglement between the qubits.

To see this more explicitly, let's try to write the Hamiltonian $H$ as a tensor product:

$$ H = H_1 \otimes H_2 = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{pmatrix}

\otimes \begin{pmatrix} e & f \\ g & h \end{pmatrix} $$

The tensor product would result in a $4 \times 4$ matrix:

$$ H = \begin{pmatrix}

a e & a f & b e & b f \\

a g & a h & b g & b h \\

c e & c f & d e & d f \\

c g & c h & d g & d h

\end{pmatrix} $$

Comparing this with the Hamiltonian $H$ we found earlier:

$$ H = \frac{\pi}{2} \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 2 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & -1

\end{pmatrix} $$

We can see that there is no way to find values for $a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h$ such that the two matrices are equal. This confirms that the Hamiltonian $H$ cannot be written as a tensor product of Hamiltonians acting on individual qubits.

JUSTIN: Up to 3 points.

A correct solution to part (b) written in the form of part (c) is ((0 0) (0 1)) \otimes pi/2 ((1 -1) (-1 1)).

This question is a bit harsh with partial/carry-through credit, but the answer also explicitly got the main idea wrong, claiming that a tensor product H cannot give an entangling unitary.

0/3.

(d) Is there an $H$ that solves (b), while also being a sum $H_1\otimes I + I\otimes H_2$ of a Hamiltonian on the first qubit and a Hamiltonian on the second qubit? Why or why not?

No, there is no Hamiltonian $H$ such that $e^{iH} = CNOT$ and $H = H_1 \otimes I + I \otimes H_2$. The reason is that the CNOT operation is an entangling operation, meaning that it creates entanglement between the two qubits. If the Hamiltonian could be written as a sum of Hamiltonians acting on individual qubits, it would not be able to create entanglement between the qubits.

To see this more explicitly, let's assume that there exists such an $H$:

$$ H = H_1 \otimes I + I \otimes H_2 = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d

\end{pmatrix} \otimes \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} +

\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \otimes \begin{pmatrix} e

& f \\ g & h \end{pmatrix} $$

The sum of the tensor products would result in a $4 \times 4$ matrix:

$$ H = \begin{pmatrix}

a + e & b & a & b \\

c & d + e & c & d \\

a & b & a + h & b \\

c & d & c & d + h

\end{pmatrix} $$

Now, we want to find an $H$ such that $e^{iH} = CNOT$. The CNOT matrix is given by:

$$ CNOT = \begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

\end{pmatrix} $$

However, there is no way to find values for $a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h$ such that $e^{iH} = CNOT$. This is because the CNOT operation creates entanglement between the qubits, and a Hamiltonian that can be written as a sum of Hamiltonians acting on individual qubits cannot create entanglement.

In summary, there is no Hamiltonian $H$ such that $e^{iH} = CNOT$ and $H = H_1 \otimes I + I \otimes H_2$ because the CNOT operation is an entangling operation, and a Hamiltonian that can be written as a sum of Hamiltonians acting on individual qubits cannot create entanglement.

Up to 4 points.

It's correct that an H of this form can't generate CNOT because it can't create entanglement, although most of the rest is just repetitive fluff.

3/4.

Now for a question about the complexity of generating certain uniform superpositions over sets (a special case of “QSampling”). Total score: 19 / 18 (of course counting extra credit).

5. In the Graph Isomorphism problem, we're given as input two $n$-vertex undirected graphs $G$ and $H$. The problem is to determine whether they're isomorphic---in other words, whether there's any permutation of the vertex labels that makes $G$ and $H$ equal.

(a) Given as input an $n$-vertex graph $G$, describe how to sample, in classical $\mathrm{poly}(n)$ time, from a probability distribution $D_G$ over graphs such that:

- Whenever the graphs $G$ and $H$ are isomorphic, $D_G = D_H$.

- Whenever $G$ and $H$ are non-isomorphic, $D_G$ and $D_H$ have disjoint supports (i.e., no graph appears with nonzero probability in both of them).

To sample from the probability distribution $D_G$ over graphs, we can follow these steps:

1. Compute the canonical form of the input graph $G$. This can be done using a graph canonization algorithm, such as the one by Brendan McKay (nauty) or the one by Laszlo Babai (Traces). These algorithms run in classical $\mathrm{poly}(n)$ time.

2. Generate a random permutation of the vertex labels of the canonical form of $G$. This can be done by selecting a random permutation of the integers from $1$ to $n$, and then applying this permutation to the vertex labels of the canonical form.

3. Apply the random permutation to the canonical form of $G$ to obtain a new graph $G'$. This graph $G'$ is a sample from the probability distribution $D_G$.

The above procedure ensures that whenever the graphs $G$ and $H$ are isomorphic, $D_G = D_H$, because their canonical forms will be the same, and the random permutations applied to their canonical forms will generate the same distribution over graphs. On the other hand, whenever $G$ and $H$ are non-isomorphic, their canonical forms will be different, and the random permutations applied to their canonical forms will generate disjoint supports for $D_G$ and $D_H$.

JUSTIN: Up to 5 points.

The first step of computing the canonical form is superfluous and incorrect, since computing the canonical form is at least as hard as solving graph isomorphism and we don't know how to solve that in polynomial time.

Also, it looks like step 2 or 3 should have been about graph H instead of both being about G.

So it seems to have exactly the right idea but described it poorly.

4/5.

(b) Given a probability distribution $D=(p_x)$ over $n$-bit strings $x$, define the ``QSampling state'' of $D$ to be $$\ket{\psi_D} := \sum_{x \in \{0,1\}^n} \sqrt{p_x} \ket{x}$$

Given two probability distributions $D$ and $D'$, suppose that the quantum circuit $\mathcal{C}$ maps $\ket{0^n}$ to $\ket{\psi_D}$, while the circuit $\mathcal{C}'$ maps $\ket{0^n}$ to $\ket{\psi_{D'}}$.

Then what is the output state of the circuit shown below, which acts on $n+1$ qubits?

$$ \Qcircuit @C=.5em @R=0.5em @!R {

\lstick{\ket{0}} & \gate{H} & \ctrl{1} & \gate{NOT} & \ctrl{1} & \qw\\

\lstick{\ket{0^n}} & \qw & \gate{\mathcal{C}} & \qw & \gate{\mathcal{C}'} & \qw } $$

To find the output state of the given circuit, we first analyze it step by step.

1. After applying the Hadamard gate (H) on the first qubit, the state becomes:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{0} + \ket{1}) \otimes \ket{0^n}$$

2. Next, the controlled-$\mathcal{C}$ gate is applied. This gate applies the $\mathcal{C}$ operation on the second register if the first qubit is in state $\ket{0}$. So, the state becomes:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{0} \otimes \ket{\psi_D} + \ket{1} \otimes \ket{0^n})$$

3. The NOT gate is applied on the first qubit, which flips the state of the first qubit. The state becomes:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{1} \otimes \ket{\psi_D} + \ket{0} \otimes \ket{0^n})$$

4. Finally, the controlled-$\mathcal{C}'$ gate is applied. This gate applies the $\mathcal{C}'$ operation on the second register if the first qubit is in state $\ket{0}$. So, the state becomes:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{1} \otimes \ket{\psi_D} + \ket{0} \otimes \ket{\psi_{D'}})$$

Thus, the output state of the circuit is:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{1} \otimes \ket{\psi_D} + \ket{0} \otimes \ket{\psi_{D'}})$$

JUSTIN: 4/4.

I think solving this one is impressive.

(c) Now suppose we measure the first qubit of that output state in the $\{\ket{+},\ket{-}\}$ basis. What is the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ if $D=D'$? What about if $D$ and $D'$ have disjoint supports?

To find the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$, we first express the output state in terms of the $\{\ket{+},\ket{-}\}$ basis. Recall that $\ket{+} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{0} + \ket{1})$ and $\ket{-} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{0} - \ket{1})$.

The output state is:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{1} \otimes \ket{\psi_D} + \ket{0} \otimes \ket{\psi_{D'}})$$

We can rewrite this state in terms of the $\{\ket{+},\ket{-}\}$ basis as follows:

$$\frac{1}{2}(\ket{+} \otimes (\ket{\psi_D} + \ket{\psi_{D'}}) + \ket{-} \otimes (\ket{\psi_D} - \ket{\psi_{D'}}))$$

Now, we can find the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ by taking the squared magnitude of the coefficient of $\ket{+}$ in the state.

Case 1: $D = D'$

In this case, $\ket{\psi_D} = \ket{\psi_{D'}}$. So, the output state becomes:

$$\frac{1}{2}(\ket{+} \otimes (2\ket{\psi_D}) + \ket{-} \otimes (0))$$

The probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ is the squared magnitude of the coefficient of $\ket{+}$, which is:

$$\left|\frac{1}{2}(2)\right|^2 = 1$$

Case 2: $D$ and $D'$ have disjoint supports

In this case, $\ket{\psi_D}$ and $\ket{\psi_{D'}}$ are orthogonal, i.e., their inner product is zero: $\langle\psi_D|\psi_{D'}\rangle = 0$. The probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ is the squared magnitude of the coefficient of $\ket{+}$, which is:

$$\left|\frac{1}{2}(\langle\psi_D|\psi_D\rangle + \langle\psi_{D'}|\psi_{D'}\rangle)\right|^2$$

Since $\langle\psi_D|\psi_D\rangle = 1$ and $\langle\psi_{D'}|\psi_{D'}\rangle = 1$ (both states are normalized), the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ is:

$$\left|\frac{1}{2}(1 + 1)\right|^2 = \frac{1}{4}(2)^2 = \frac{1}{2}$$

So, if $D = D'$, the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ is 1, and if $D$ and $D'$ have disjoint supports, the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ is $\frac{1}{2}$.

SCOTT: HOLY CRAP, LOOKS CORRECT!

JUSTIN: 5/5.

(d) Suppose your distributions $D_G$ from part (a) could be efficiently QSampled. Using your previous work, explain how Graph Isomorphism could then be solved in $BQP$ (quantum polynomial time).

Suppose we can efficiently QSample the distributions $D_G$ and $D_H$ for two input graphs $G$ and $H$. We can then construct the QSampling states $\ket{\psi_{D_G}}$ and $\ket{\psi_{D_H}}$ for these distributions using the quantum circuits $\mathcal{C}_G$ and $\mathcal{C}_H$, respectively, as described in the previous problems.

Now, consider the following quantum circuit acting on $n+1$ qubits:

$$ \Qcircuit @C=.5em @R=0.5em @!R { \lstick{\ket{0}} & \gate{H} & \ctrl{1} & \gate{NOT} & \ctrl{1} & \qw\\ \lstick{\ket{0^n}} & \qw & \gate{\mathcal{C}_G} & \qw & \gate{\mathcal{C}_H} & \qw } $$

As we found earlier, the output state of this circuit is:

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\ket{1} \otimes \ket{\psi_{D_G}} + \ket{0} \otimes \ket{\psi_{D_H}})$$

Now, we measure the first qubit of the output state in the $\{\ket{+},\ket{-}\}$ basis. We know from our previous work that if $G$ and $H$ are isomorphic (i.e., $D_G = D_H$), the probability of the outcome $\ket{+}$ is 1, and if $G$ and $H$ are non-isomorphic (i.e., $D_G$ and $D_H$ have disjoint supports), the probability of the

outcome $\ket{+}$ is $\frac{1}{2}$.

Thus, we can solve the Graph Isomorphism problem in $BQP$ as follows:

1. Construct the QSampling states $\ket{\psi_{D_G}}$ and $\ket{\psi_{D_H}}$ for the input graphs $G$ and $H$ using the quantum circuits $\mathcal{C}_G$ and $\mathcal{C}_H$.

2. Implement the above quantum circuit and measure the first qubit in the $\{\ket{+},\ket{-}\}$ basis.

3. If the outcome is $\ket{+}$ with probability close to 1, conclude that the graphs $G$ and $H$ are isomorphic. If the outcome is $\ket{+}$ with probability close to $\frac{1}{2}$, conclude that the graphs $G$ and $H$ are non-isomorphic.

This algorithm runs in quantum polynomial time, as the QSampling circuits $\mathcal{C}_G$ and $\mathcal{C}_H$ are assumed to be efficient, and the rest of the operations (Hadamard, NOT, and controlled gates) are also efficient.

JUSTIN: The answer is longer than necessary, repeating some of its previous work.

Also, in theory, if the graphs are isomorphic then the probability of |+> will be exactly 1 not close to 1.

4/4.

(e) So then why doesn't this approach immediately imply a fast quantum algorithm for Graph Isomorphism? Explain what could go wrong in passing from fast algorithms to sample $D_G$ and $D_H$, to fast algorithms to QSample them.

The approach described above does not immediately imply a fast quantum algorithm for Graph Isomorphism because there is a crucial difference between classical sampling and QSampling.

In the algorithm, we assumed that we can efficiently construct quantum circuits $\mathcal{C}_G$ and $\mathcal{C}_{G'}$ that map $\ket{0^n}$ to $\ket{\psi_{D_G}}$ and $\ket{\psi_{D_{G'}}}$, respectively, given that the distributions $D_G$ and $D_{G'}$ can be efficiently sampled classically. However, this assumption might not hold in general.

Classical sampling allows us to draw samples from the distributions $D_G$ and $D_{G'}$, but it does not directly provide a way to prepare the corresponding QSampling states $\ket{\psi_{D_G}}$ and $\ket{\psi_{D_{G'}}}$. Preparing these quantum states requires a coherent superposition of all the elements in the distributions with the appropriate amplitudes, which might not be efficiently achievable using the classical sampling algorithms.

In other words, the ability to efficiently sample from a probability distribution classically does not necessarily imply the ability to efficiently prepare the corresponding QSampling state on a quantum computer. This is the main reason why the approach does not immediately lead to a fast quantum algorithm for Graph Isomorphism.

SCOTT: Correctly explains that sampling doesn't necessarily imply QSampling (i.e. generating a coherent superposition state), but doesn't say that this is because of the difficulty of uncomputing garbage.

2 / 5 extra credit points.

Next, a problem about quantum communication complexity. Total score: 5 / 10.

6. Suppose Alice and Bob hold $n$-bit strings $x=(x_1,...,x_n)$ and $y=(y_1,...,y_n)$ respectively. One thing they might want to learn is the mod-2 inner product of their strings, $$x_1 y_1 + \ldots + x_n y_n (\bmod 2).$$

(a) Suppose Alice and Bob had a quantum communication protocol in which they are allowed to exchange up to $T$ qubits and to perform arbitrary local unitary transformations to their qubits (possibly including ancilla qubits), that ended with Bob knowing the above inner product, with success probability 1. Explain how, by exchanging the same number of qubits $T$, Bob could also prepare an $n$-qubit state

of the form $$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{x\cdot z} \ket{z},$$

where $x$ is an $n$-bit string held by Alice.

If Alice and Bob have a quantum communication protocol that allows Bob to know the mod-2 inner product of their strings with success probability 1, then they can use the same protocol to prepare the desired $n$-qubit state.

Here's how they can do it:

1. Alice prepares an $n$-qubit state $\ket{\phi}$, where

$$\ket{\phi} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} \ket{z}.$$

2. Alice applies a controlled-phase gate to each qubit of $\ket{\phi}$, using her $n$-bit string $x$ as the control. This results in the state

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{x\cdot z} \ket{z}.$$

3. Alice sends the $n$-qubit state to Bob.

4. Bob uses the quantum communication protocol to learn the mod-2 inner product of their strings. Since the protocol has success probability 1, Bob will know the inner product with certainty.

5. Bob applies a local unitary transformation to the $n$-qubit state he received from Alice, based on the inner product he learned in step 4. This will result in the desired state

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{x\cdot z} \ket{z}.$$

Since Alice and Bob only exchanged $T$ qubits in the original protocol, they can also prepare the desired $n$-qubit state by exchanging the same number of qubits $T$.

JUSTIN: Up to 4 points.

This answer is partially correct and/or poorly worded. In particular, in step 3 Alice just sends the whole n-qubit state to Bob.

The right idea is in there, but doesn't earn full points.

2/4.

(b) Assume Alice and Bob have no preshared entanglement. Recall Holevo's Theorem, which implies that in order to communicate $n$ bits to Bob reliably, Alice must send Bob at least $n$ qubits. Using Holevo's Theorem together with part (a), prove that Alice and Bob must exchange at least $n$ qubits, even if they only want to learn the inner product mod 2 of their input strings $x$ and $y$.

From part (a), we know that if Alice and Bob have a quantum communication protocol that allows Bob to know the mod-2 inner product of their strings with success probability 1, then they can also prepare an $n$-qubit state of the form

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{x\cdot z} \ket{z},$$

by exchanging the same number of qubits $T$.

Now, let's consider the reverse process. Suppose Bob has the $n$-qubit state

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{x\cdot z} \ket{z}.$$

He can perform a quantum measurement in the computational basis to obtain a random $n$-bit string $z$. Then, he can compute the mod-2 inner product $x \cdot z$ and send it back to Alice.

Alice, knowing her own string $x$, can compute the mod-2 inner product $x \cdot z$ as well. If the inner product $x \cdot z$ that Bob sent to Alice matches the one she computed, then they have successfully communicated the inner product mod 2 of their input strings $x$ and $y$.

However, according to Holevo's Theorem, in order to communicate $n$ bits to Bob reliably, Alice must send Bob at least $n$ qubits. Since the $n$-qubit state prepared in part (a) effectively communicates $n$ bits of information (Alice's string $x$) to Bob, Holevo's Theorem implies that Alice and Bob must exchange at least $n$ qubits to prepare this state.

Therefore, even if Alice and Bob only want to learn the inner product mod 2 of their input strings $x$ and $y$, they must exchange at least $n$ qubits.

JUSTIN: Up to 6 points.

This answer doesn't earn any points. It only says that Alice and Bob learn the inner products and mistakenly claims this is n bits of information.

The correct solution recognizes that applying Hadamard to the state we showed how to prepare in part (a) gives exactly |x>.

0/6.

(c) Now suppose we're no longer working mod 2, and Alice and Bob want to know whether their inner product

$$x_1 y_1 + \ldots + x_n y_n$$

is zero or nonzero as an integer. (In other words, whether there's an $i$ such that $x_i=y_i=1$.) Describe a protocol by which Alice and Bob can accomplish this, with high probability, by exchanging only $O(\sqrt{n}\log n )$ qubits in total. The qubits can be spread across as many rounds of communication as necessary, and can be sent in either direction.

Alice and Bob can use the following protocol, based on the Grover's search algorithm, to determine whether their inner product is zero or nonzero as an integer, with high probability, by exchanging only $O(\sqrt{n}\log n)$ qubits in total:

1. Alice prepares a quantum register of $n$ qubits in the state $\ket{0}^{\otimes n}$.

2. Alice applies the Hadamard gate to each qubit, resulting in the state $$\ket{\psi} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} \ket{z}.$$

3. Alice and Bob perform the following steps for $O(\sqrt{n})$ iterations:

a. Alice sends the $n$-qubit state $\ket{\psi}$ to Bob.

b. Bob applies a controlled-phase gate to each qubit of $\ket{\psi}$, using his $n$-bit string $y$ as the control. This results in the state

$$\ket{\psi'} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{y\cdot z} \ket{z}.$$

c. Bob sends the $n$-qubit state $\ket{\psi'}$ back to Alice.

d. Alice applies a controlled-phase gate to each qubit of $\ket{\psi'}$, using her $n$-bit string $x$ as the control. This results in the state

$$\ket{\psi''} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2^n}} \sum_{z \in \{0,1\}^n} (-1)^{(x+y)\cdot z} \ket{z}.$$

Note that if $x_i = y_i = 1$ for some $i$, then the phase of the corresponding term in the sum will be flipped twice, resulting in no change. Therefore, the state $\ket{\psi''}$ will have a non-zero amplitude for the terms corresponding to the indices where $x_i = y_i = 1$.

e. Alice applies the Grover's diffusion operator to the state $\ket{\psi''}$, which amplifies the amplitudes of the terms corresponding to the indices where $x_i = y_i = 1$. The diffusion operator can be implemented as follows:

- Apply the Hadamard gate to each qubit.

- Apply a multi-qubit controlled-Z gate, with all qubits as controls and an ancilla qubit as the target.

- Apply the Hadamard gate to each qubit again.

f. Alice updates the state $\ket{\psi}$ with the resulting state after applying the Grover's diffusion operator.

4. After $O(\sqrt{n})$ iterations, Alice measures the final state in the computational basis. If she obtains a non-zero result, then there exists an $i$ such that $x_i = y_i = 1$, and their inner product is nonzero as an integer. If she obtains a zero result, then their inner product is zero.

Since Alice and Bob exchange $n$ qubits in each iteration, and they perform $O(\sqrt{n})$ iterations, the total number of qubits exchanged is $O(n\sqrt{n}) = O(\sqrt{n}\log n)$, as each qubit can represent $\log n$ bits of information. Thus, Alice and Bob can determine whether their inner product is zero or nonzero as an integer, with high probability, by exchanging only $O(\sqrt{n}\log n)$ qubits in total.

SCOTT: LOOKS BASICALLY RIGHT, EXCEPT FOR A SLIP-UP AT THE END WHERE IT SAYS

ALICE AND BOB EXCHANGE n QUBITS PER ITERATION RATHER THAN log n ...

JUSTIN: Up to 6 extra credit points.

Yeah, step 3a says it's sending n qubits, when it's actually log n.

It also seems incorrect beginning in the analysis of step d. It switches from summing over |z> and referring to the full strings x and y to referring to individual indices i,x_i,y_i. And I don't know what it means about some amplitudes going to zero since what we're really doing is having some amplitudes be +1 and some -1.

I don't think this protocol is correct as stated.

But, it has some of the main ideas. The analysis of the grover steps is good and using a phase gate is good.

3/6 extra credit.

OK, last question, about the k-SUM problem. Total score: 6 / 15.

7. In the famous $k$-SUM problem, we're given a list of integers $x_1,\ldots,x_n$, and are asked whether there are $k$ distinct indices, $i_1 < \ldots < i_k$, such that $x_{i_1} + \ldots + x_{i_k} = 0$.

For this problem, you can ignore factors of $\log n$ in the running time (indeed, that is what the $\widetilde{O}$ notation means).

(a) Assume $k$ is even AND that we are allowed multi-sets (aka repeated elements are allowed). Describe a classical algorithm that solves the $k$-SUM problem in $\widetilde{O}(n^{k/2})$ time, beating the trivial upper bound of $\widetilde{O}(n^k)$.

We can solve the k-SUM problem in $\widetilde{O}(n^{k/2})$ time using a meet-in-the-middle approach. Here's a high-level description of the algorithm:

1. Divide the list of integers into two equal halves: $A = x_1, \ldots, x_{n/2}$ and $B = x_{n/2+1}, \ldots, x_n$.

2. Compute all possible sums of $k/2$ elements from each half. For each half, this can be done in $O(n^{k/2})$ time by iterating through all possible combinations of $k/2$ elements.

3. Sort the lists of sums for both halves. This can be done in $O(n^{k/2} \log n)$ time using a comparison-based sorting algorithm.

4. For each sum in the first half, perform a binary search in the second half to find a sum that is equal to the negation of the sum from the first half. If such a sum is found, then we have found k distinct indices whose elements sum to 0. Binary search takes $O(\log n)$ time, so this step takes $O(n^{k/2} \log n)$ time.

Since we are ignoring factors of $\log n$, the overall running time of the algorithm is $\widetilde{O}(n^{k/2})$.

SCOTT: LOOKS LIKE IT WOULD WORK *IF* WE KNEW THE k-SET WAS EQUALLY BALANCED

BETWEEN THE LEFT AND RIGHT HALVES...

JUSTIN: Up to 5 points.

Right, step 1 is incorrect. Instead, it should generate all O(n^{k/2}) sums of subsets of size k/2. Nothing about dividing into two halves.

4/5.

(b) Assume $k$ is divisible by 3 and that we are again allowed multi-sets. Describe a quantum algorithm that solves the $k$-SUM problem in $\widetilde{O}(n^{k/3})$ time.

We can solve the k-SUM problem in $\widetilde{O}(n^{k/3})$ time using a quantum algorithm based on Grover's search. Here's a high-level description of the algorithm:

1. Divide the list of integers into three equal parts: $A = x_1, \ldots, x_{n/3}$, $B = x_{n/3+1}, \ldots, x_{2n/3}$, and $C = x_{2n/3+1}, \ldots, x_n$.

2. Compute all possible sums of $k/3$ elements from each part. For each part, this can be done in $O(n^{k/3})$ time by iterating through all possible combinations of $k/3$ elements.

3. Sort the lists of sums for all three parts. This can be done in $O(n^{k/3} \log n)$ time using a comparison-based sorting algorithm.

4. Define an oracle function $f$ that takes as input a sum from the first part and a sum from the second part, and returns 1 if there exists a sum in the third part that is equal to the negation of the sum of the inputs, and 0 otherwise. This oracle can be implemented using a binary search on the sorted list of sums for the third part, which takes $O(\log n)$ time.

5. Use Grover's search algorithm to find a pair of sums from the first and second parts that satisfy the oracle function. Grover's search has a quadratic speedup over classical search, so it takes $O(\sqrt{n^{k/3}}) = O(n^{k/6})$ time.

Since we are ignoring factors of $\log n$, the overall running time of the algorithm is $\widetilde{O}(n^{k/3})$.

JUSTIN: Up to 5 points.

Again, step 1 is incorrect, it shouldn't divide into three parts.

The division into three parts is more problematic this time as it comes up in step 4.

And it ends up claiming n^{k/6] time in step 5, better than the n^{k/3}.

Basically all this gets correct is to use Grover in some way.

1/5.

(c) Suppose we wanted to prove that the algorithm from (b) was the fastest possible quantum algorithm for $k$-SUM. Could that be shown via a lower bound on $k$-SUM's quantum query complexity? Why or why not?

Proving that the algorithm from (b) is the fastest possible quantum algorithm for k-SUM would require showing a lower bound on k-SUM's quantum query complexity that matches the upper bound achieved by the algorithm. However, a lower bound on the quantum query complexity alone might not be sufficient to prove the optimality of the algorithm, as it only considers the number of queries to the oracle function and does not account for other computational resources, such as time or space complexity.

To show that the algorithm from (b) is the fastest possible quantum algorithm for k-SUM, one would need to establish a lower bound on the quantum time complexity or some other relevant complexity measure that matches the upper bound achieved by the algorithm. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the problem's inherent difficulty and the limitations of quantum algorithms in solving it.

JUSTIN: Up to 5 extra credit points.

This is a nice description of query vs time complexity, but misses the point that query complexity can prove a bound of at most Omega(n) since there are at most n potential queries to make.

1/5 extra credit points.

Follow

Follow