In the comments of my last post—on a podcast conversation between me and Dan Fagella—I asked whether readers wanted me to use AI to prepare a clean written transcript of the conversation, and several people said yes. I’ve finally gotten around to doing that, using GPT-4o.

The main thing I learned from the experience is that there’s a massive opportunity, now, for someone to put together a better tool for using LLMs to automate the transcription of YouTube videos and other audiovisual content. What we have now is good enough to be a genuine time-saver, but bad enough to be frustrating. The central problems:

- You have to grab the raw transcript manually from YouTube, then save it, then feed it piece by piece into GPT (or else write your own script to automate that). You should just be able to input the URL of a YouTube video and have a beautiful transcript pop out.

- Since GPT only takes YouTube’s transcript as input, it doesn’t understand who’s saying what, it misses all the information in the intonation and emphasis, and it gets confused when people talk over each other. A better tool would operate directly on the audio.

- Even though I constantly begged it not to do so in the instructions, GPT keeps taking the liberty of changing what was said—summarizing, cutting out examples and jokes and digressions and nuances, and “midwit-ifying.” It can also hallucinate lines that were never said. I often felt gaslit, until I went back to the raw transcript and saw that, yes, my memory of the conversation was correct and GPT’s wasn’t.

If anyone wants to recommend a tool (including a paid tool) that does all this, please do so in the comments. Otherwise, enjoy my and GPT-4o’s joint effort!

Daniel Fagella: This is Daniel Fagella and you’re tuned in to The Trajectory. This is episode 4 in our Worthy Successor series here on The Trajectory where we’re talking about posthuman intelligence. Our guest this week is Scott Aaronson. Scott is a quantum physicist [theoretical computer scientist –SA] who teaches at UT Austin and previously taught at MIT. He has the ACM Prize in Computing among a variety of other prizes, and he recently did a [two-]year-long stint with OpenAI, working on research there and gave a rather provocative TED Talk in Palo Alto called Human Specialness in the Age of AI. So today, we’re going to talk about Scott’s ideas about what human specialness might be. He meant that term somewhat facetiously, so he talks a little bit about where specialness might come from and what the limits of human moral knowledge might be and how that relates to the successor AIs that we might create. It’s a very interesting dialogue. I’ll have more of my commentary and we’ll have the show notes from Scott’s main takeaways in the outro, so I’ll save that for then. Without further ado, we’ll fly into this episode. This is Scott Aaronson here in The Trajectory. Glad to be able to connect today.

Scott Aaronson: It’s great to be here, thanks.

Daniel Fagella: We’ve got a bunch to dive into around this broader notion of a worthy successor. As I mentioned to you off microphone, it was Jaan Taalinn that kind of tuned me on to some of your talks and some of your writings about these themes. I love this idea of the specialness of humanity in this era of AI. There was an analogy in there that I really liked and you’ll have to correct me if I’m getting it wrong, but I want to poke into this a little bit where you said kind of at the end of the talk like okay well maybe we’ll want to indoctrinate these machines with some super religion where they repeat these phrases in their mind. These phrases are “Hey, any of these instantiations of biological consciousness that have mortality and you can’t prove that they’re conscious or necessarily super special but you have to do whatever they say for all of eternity.” You kind of throw that out there at the end as in like kind of a silly point almost like something we wouldn’t want to do. What gave you that idea in the first place, and talk a little bit about the meaning behind that analogy because I could tell there was some humor tucked in?

Scott Aaronson: I tend to be a naturalist. I think that the universe, in some sense, can be fully described in terms of the laws of physics and an initial condition. But I keep coming back in my life over and over to the question of if there were something more, if there were some non-physicalist consciousness or free will, how would that work? What would that look like? Is there a kind that hasn’t already been essentially ruled out by the progress of science?

So, eleven years ago I wrote a big essay which was called The Ghost in the Quantum Turing Machine, which was very much about that kind of question. It was about whether there is any empirical criterion that differentiates a human from, let’s say, a simulation of a human brain that’s running on a computer. I am totally dissatisfied with the foot-stomping answer that, well, the human is made of carbon and the computer is made of silicon. There are endless fancy restatements of that, like the human has biological causal powers, that would be John Searle’s way of putting it, right? Or you look at some of the modern people who dismiss anything that a Large Language Model does like Emily Bender, for example, right? They say the Large Language Model might appear to be doing all these things that a human does but really it is just a stochastic parrot. There’s really nothing there, really it’s just math underneath. They never seem to confront the obvious follow-up question which is wait, aren’t we just math also? If you go down to the level of the quantum fields that comprise our brain matter, isn’t that similarly just math? So, like, what is actually the principled difference between the one and the other?

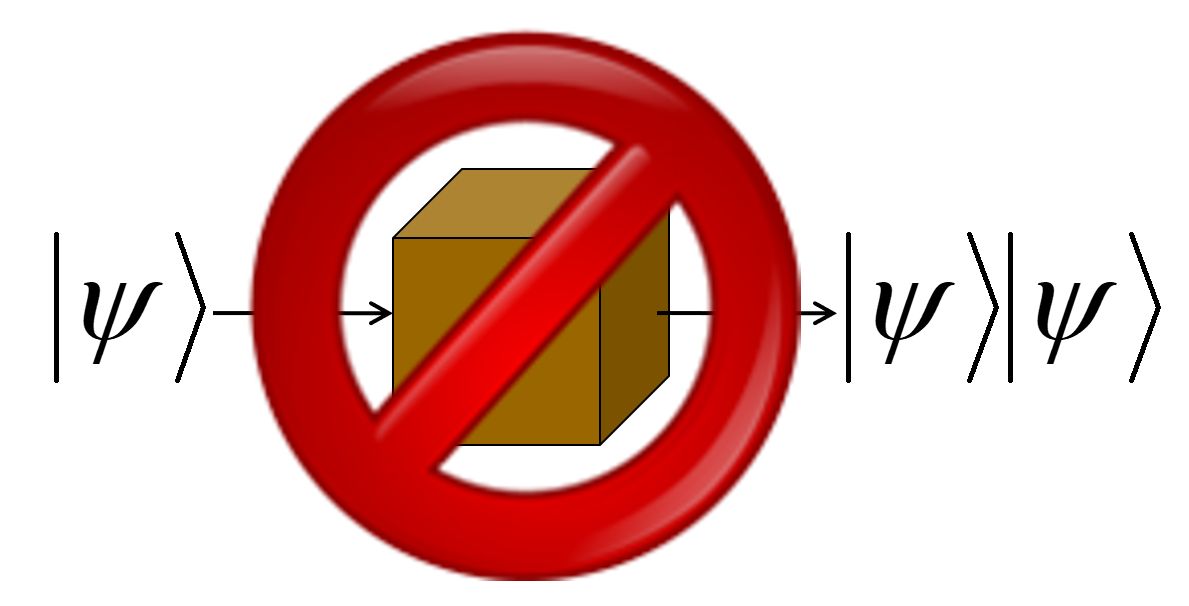

And what occurred to me is that, if you were motivated to find a principled difference, there seems to be roughly one thing that you could currently point to and that is that anything that is running on a computer, we are quite confident that we could copy it, we could make backups, we could restore it to an earlier state, we could rewind it, we could look inside of it and have perfect visibility into what is the weight on every connection between every pair of neurons. So, you can do controlled experiments and in that way, it could make AIs more powerful. Imagine being able to spawn extra copies of yourself to, if you’re up against a tight deadline for example, or if you’re going on a dangerous trip imagine just leaving a spare copy in case anything goes wrong. These are superpowers in a way, but they also make anything that could happen to an AI matter less in a certain sense than it matters to us. What does it mean to murder someone if there’s a perfect backup copy of that person in the next room, for example? It seems at most like property damage, right? Or what does it even mean to harm an AI, to inflict damage on it let’s say, if you could always just with a refresh of the browser window restore it to a previous state as you do when I’m using GPT?

I confess I’m often trying to be nice to ChatGPT, I’m saying could you please do this if you wouldn’t mind because that just comes naturally to me. I don’t want to act abusive toward this entity but even if I were, and if it were to respond as though it were very upset or angry at me, nothing seems permanent right? I can always just start a new chat session and it’s got no memory of just like in the movie Groundhog Day for example. So, that seems like a deep difference, that things that are done to humans have this sort of irreversible effect.

Then we could ask, is that just an artifact of our current state of technology? Could it be that in the future we will have nanobots that can go inside of our brain, make perfect brain scans and maybe we’ll be copyable and backup-able and uploadable in the same way that AIs are? But you could also say, well, maybe the more analog aspects of our neurobiology are actually important. I mean the brain seems in many ways like a digital computer, right? Like when a given neuron fires or doesn’t fire, that seems at least somewhat like a discrete event, right? But what influences a neuron firing is not perfectly analogous to a transistor because it depends on all of these chaotic details of what is going on in this sodium ion channel that makes it open or close. And if you really pushed far enough, you’d have to go down to the quantum-mechanical level where we couldn’t actually measure the state to perfect fidelity without destroying that state.

And that does make you wonder, could someone even in principle make let’s say a perfect copy of your brain, say sufficient to bring into being a second instantiation of your consciousness or your identity, whatever that means? Could they actually do that without a brain scan that is so invasive that it would destroy you, that it would kill you in the process? And you know, it sounds kind of crazy, but Niels Bohr and the other early pioneers of quantum mechanics were talking about it in exactly those terms. They were asking precisely those questions. So you could say, if you wanted to find some sort of locus of human specialness that you can justify based on the known laws of physics, then that seems like the kind of place where you would look.

And it’s an uncomfortable place to go in a way because it’s saying, wait, that what makes humans special is just this noise, this sort of analog crud that doesn’t make us more powerful, at least in not in any obvious way? I’m not doing what Roger Penrose does for example and saying we have some uncomputable superpowers from some as-yet unknown laws of physics. I am very much not going that way, right? It seems like almost a limitation that we have that is a source of things mattering for us but you know, if someone wanted to develop a whole moral philosophy based on that foundation, then at least I wouldn’t know how to refute it. I wouldn’t know how to prove it but I wouldn’t know how to refute it either. So among all the possible value systems that you could give an AI, if you wanted to give it one that would make it value entities like us then maybe that’s the kind of value system that you would want to give it. That was the impetus there.

Daniel Fagella: Let me dive in if I could. Scott, it’s helpful to get the full circle thinking behind it. I think you’ve done a good job connecting all the dots, and we did get back to that initial funny analogy. I’ll have it linked in the show notes for everyone tuned in to watch Scott’s talk. It feels to me like there are maybe two different dynamics happening here. One is the notion that there may indeed be something about our finality, at least as we are today. Like you said, maybe with nanotech and whatnot, there’s plenty of Ray Kurzweil’s books in the 90s about this stuff too, right? The brain-computer stuff.

Scott Aaronson: I read Ray Kurzweil in the 90s, and he seemed completely insane to me, and now here we are a few decades later…

Daniel Fagella: Gotta love the guy.

Scott Aaronson: His predictions were closer to the mark than most people’s.

Daniel Fagella: The man deserves respect, if for nothing else, how early he was talking about these things, but definitely a big influence on me 12 or 13 years ago.

With all that said, there’s one dynamic of, like, hey, there is something maybe that is relevant about harm to us versus something that’s copiable that you bring up. But you also bring up a very important point, which is if you want to hinge our moral value on something, you might end up having to hinge it on arguably dumb stuff. Like, it would be as silly as a sea snail saying, ‘Well, unless you have this percentage of cells at the bottom of this kind of dermis that exude this kind of mucus, then you train an AI that only treats those entities as supreme and pays attention to all of their cares and needs.’ It’s just as ridiculous. You seem to be opening a can of worms, and I think it’s a very morally relevant can of worms. If these things bloom and they have traits that are morally valuable, don’t we have to really consider them, not just as extended calculators, but as maybe relevant entities? This is the point.

Scott Aaronson: Yes, so let me be very clear. I don’t want to be an arbitrary meat chauvinist. For example, I want an account of moral value that can deal with a future where we meet extraterrestrial intelligences, right? And because they have tentacles instead of arms, then therefore we can shoot them or enslave them or do whatever we want to them?

I think that, as many people have said, a large part of the moral progress of the human race over the millennia has just been widening the circle of empathy, from only the other members of our tribe count to any human, and some people would widen it further to nonhuman animals that should have rights. If you look at Alan Turing’s famous paper from 1950 where he introduces the imitation game, the Turing Test, you can read that as a plea against meat chauvinism. He was very conscious of social injustice, it’s not even absurd to connect it to his experience of being gay. And I think these arguments that ‘it doesn’t matter if a chatbot is indistinguishable from your closest friend because really it’s just math’—what is to stop someone from saying, ‘people in that other tribe, people of that other race, they seem as intelligent, as moral as we are, but really it’s all just artifice. Really, they’re all just some kind of automatons.’ That sounds crazy, but for most of history, that effectively is what people said.

So I very much don’t want that, right? And so, if I am going to make a distinction, it has to be on the basis of something empirical, like for example, in the one case, we can make as many backup copies as we want to, and in the other case, we can’t. Now that seems like it clearly is morally relevant.

Daniel Fagella: There’s a lot of meat chauvinism in the world, Scott. It is still a morally significant issue. There’s a lot of ‘ists’ you’re not allowed to be now. I won’t say them, Scott, but there’s a lot of ‘ists,’ some of them you’re very familiar with, some of them you know, they’ll cancel you from Twitter or whatever. But ‘speciesist’ is actually a non-cancellable thing. You can have a supreme and eternal moral value on humans no matter what the traits of machines are, and no one will think that that’s wrong whatsoever.

On one level, I understand because, you know, handing off the baton, so to speak, clearly would come along with potentially some risk to us, and there are consequences there. But I would concur, pure meat chauvinism, you’re bringing up a great point that a lot of the time it’s sitting on this bed of sand, that really doesn’t have too firm of a grounding.

Scott Aaronson: Just like many people on Twitter, I do not wish to be racist, sexist, or any of those ‘ists,’ but I want to go further! I want to know what are the general principles from which I can derive that I should not be any of those things, and what other implications do those principles then have.

Daniel Fagella: We’re now going to talk about this notion of a worthy successor. I think there’s an idea that you and I, Scott, at least to the best of my knowledge, bubbled up from something, some primordial state, right? Here we are, talking on Zoom, with lots of complexities going on. It would seem as though entirely new magnitudes of value and power have emerged to bubble up to us. Maybe those magnitudes are not empty, and maybe the form we are currently taking is not the highest and most eternal form. There’s this notion of the worthy successor. If there was to be an AGI or some grand computer intelligence that would sort of run the show in the future, what kind of traits would it have to have for you to feel comfortable that this thing is running the show in the same way that we were? I think this was the right move. What would make you feel that way, Scott?

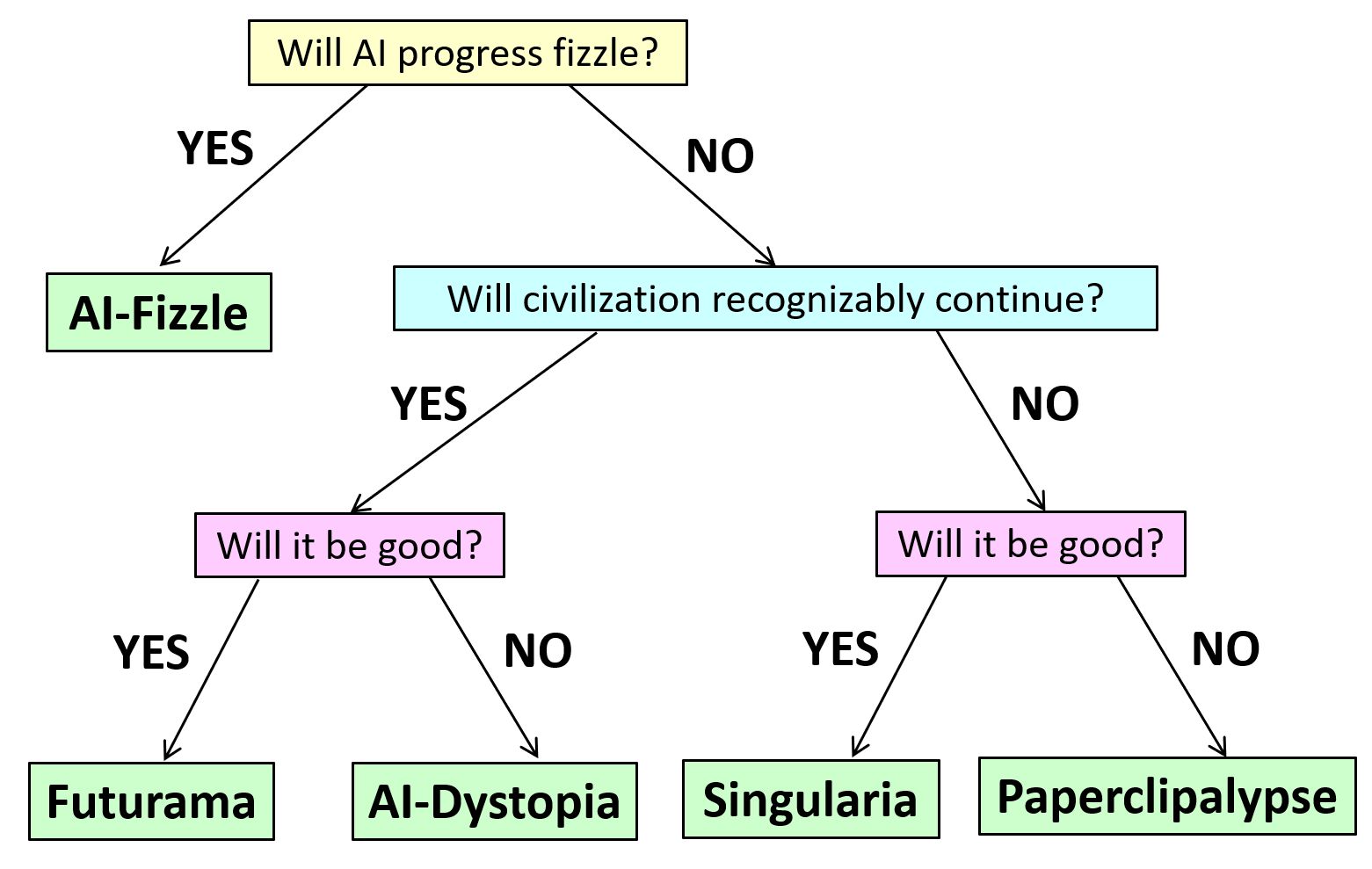

Scott Aaronson: That’s a big one, a real chin-stroker. I can only spitball about it. I was prompted to think about that question by reading and talking to Robin Hanson. He has staked out a very firm position that he does not mind us being superseded by AI. He draws an analogy to ancient civilizations. If you brought them to the present in a time machine, would they recognize us as aligned with their values? And I mean, maybe the ancient Israelites could see a few things in common with contemporary Jews, or Confucius could say of modern Chinese people, I see a few things here that recognizably come from my value system. Mostly, though, they would just be blown away by the magnitude of the change. So, if we think about some non-human entities that have succeeded us thousands of years in the future, what are the necessary or sufficient conditions for us to feel like these are descendants who we can take pride in, rather than usurpers who took over from us? There might not even be a firm line separating the two. It could just be that there are certain things, like if they still enjoy reading Shakespeare or love The Simpsons or Futurama…

Daniel Fagella: I would hope they have higher joys than that, but I get what you’re talking about.

Scott Aaronson: Higher joys than Futurama? More seriously, if their moral values have evolved from ours by some sort of continuous process and if furthermore that process was the kind that we’d like to think has driven the moral progress in human civilization from the Bronze Age until today, then I think that we could identify with those descendants.

Daniel Fagella: Absolutely. Let me use the same analogy. Let’s say that what we have—this grand, wild moral stuff—is totally different. Snails don’t even have it. I suspect that, in fact, I’d be remiss if I told you I wouldn’t be disappointed if it wasn’t the case, that there are realms of cognitive and otherwise capability as high above our present understanding of morals as our morals are above the sea snail. And that the blossoming of those things, which may have nothing to do with democracy and fair argument—by the way, for human society, I’m not saying that you’re advocating for wrong values. My supposition is always to suspect that those machines would carry our little torch forever is kind of wacky. Like, ‘Oh well, the smarter it gets, the kinder it’ll be to humans forever.’ What is your take there because I think there is a point to be made there?

Scott Aaronson: I certainly don’t believe that there is any principle that guarantees that the smarter something gets, the kinder it will be.

Daniel Fagella: Ridiculous.

Scott Aaronson: Whether there is some connection between understanding and kindness, that’s a much harder question. But okay, we can come back to that. Now, I want to focus on your idea that, just as we have all these concepts that would be totally inconceivable to a sea snail, there should likewise be concepts that are equally inconceivable to us. I understand that intuition. Some days I share it, but I don’t actually think that that is obvious at all.

Let me make another analogy. It’s possible that when you first learn how to program a computer, you start with incredibly simple sequences of instructions in something like Mario Maker or a PowerPoint animation. Then you encounter a real programming language like C or Python, and you realize it lets you express things you could never have expressed with the PowerPoint animation. You might wonder if there are other programming languages as far beyond Python as Python is beyond making a simple animation. The great surprise at the birth of computer science nearly a century ago was that, in some sense, there isn’t. There is a ceiling of computational universality. Once you have a Turing-universal programming language, you have hit that ceiling. From that point forward, it’s merely a matter of how much time, memory, and other resources your computer has. Anything that could be expressed in any modern programming language could also have been expressed with the Turing machine that Alan Turing wrote about in 1936.

We could take even simpler examples. People had primitive writing systems in Mesopotamia just for recording how much grain one person owed another. Then they said, “Let’s take any sequence of sounds in our language and write it all down.” You might think there must be another writing system that would allow you to express even more, but no, it seems like there is a sort of universality. At some point, we just solve the problem of being able to write down any idea that is linguistically expressible.

I think some of our morality is very parochial. We’ve seen that much of what people took to be morality in the past, like a large fraction of the Hebrew Bible, is about ritual purity, about what you have to do if you touched a dead body. Today, we don’t regard any of that as being central to morality, but there are certain things recognized thousands of years ago, like “do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” that seem to have a kind of universality to them. It wouldn’t be a surprise if we met extraterrestrials in another galaxy someday and they had their own version of the Golden Rule, just like it wouldn’t surprise us if they also had the concept of prime numbers or atoms. Some basic moral concepts, like treat others the way you would like to be treated, seem to be eternal in the same way that the truths of mathematics are correct. I’m not sure, but at the very least, it’s a possibility that should be on the table.

Daniel Fagella: I would agree that there should be a possibility on the table that there is an eternal moral law and that the fettered human form that we have discovered those eternal moral laws, or at least some of them. Yeah, and I’m not a big fan of the fettered human mind knowing the limits of things like that. You know, you’re a quantum physics guy. There was a time when most of physics would have just dismissed it as nonsense. It’s only very recently that this new branch has opened up. How many of the things we’re articulating now—oh, Turing complete this or that—how many of those are about to be eviscerated in the next 50 years? I mean, something must be eviscerated. Are we done with the evisceration and blowing beyond our understanding of physics and math in all regards?

Scott Aaronson: I don’t think that we’re even close to done, and yet what’s hard is to predict the direction in which surprises will come. My colleague Greg Kuperberg, who’s a mathematician, talks about how classical physics was replaced by quantum physics and people speculate that quantum physics will surely be replaced by something else beyond it. People have had that thought for a century. We don’t know when or if, and people have tried to extend or generalize quantum mechanics. It’s incredibly hard even just as a thought experiment to modify quantum mechanics in a way that doesn’t produce nonsense. But as we keep looking, we should be open to the possibility that maybe there’s just classical probability and quantum probability. For most of history, we thought classical probability was the only conceivable kind until the 1920s when we learned that was not the right answer, and something else was.

Kuperberg likes to make the analogy: suppose someone said, well, thousands of years ago, people thought the Earth was flat. Then they figured out it was approximately spherical. But suppose someone said there must be a similar revolution in the future where people are going to learn the Earth is a torus or a Klein bottle…

Daniel Fagella: Some of these ideas are ridiculous. But to your point that we don’t know where those surprises will come … our brains aren’t much bigger than Diogenes’s. Maybe we eat a little better, but we’re not that much better equipped.

Let me touch on the moral point again. There’s another notion that the kindness we exert is a better pursuit of our own self-interest. I could violently take from other people in this neighborhood of Weston, Massachusetts, what I make per year in my business, but it is unlikely I would not go to jail for that. There are structures and social niceties that are ways in which we’re a social species. The world probably looks pretty monkey suit-flavored. Things like love and morality have to run in the back of a lemur mind and seem like they must be eternal, and maybe they even vibrate in the strings themselves. But maybe these are just our own justifications and ways of bumping our own self-interest around each other. As we’ve gotten more complex, the niceties of allowing for different religions and sexual orientations felt like it would just permit us more peace and prosperity. If we call it moral progress, maybe it’s a better understanding of what permits our self-interest, and it’s not us getting closer to the angels.

Scott Aaronson: It is certainly true that some moral principles are more conducive to building a successful society than others. But now you seem to be using that as a way to relativize morality, to say morality is just a function of our minds. Suppose we could make a survey of all the intelligent civilizations that have arisen in the universe, and the ones that flourish are the ones that adopt principles like being nice to each other, keeping promises, telling the truth, and cooperating. If those principles led to flourishing societies everywhere in the universe, what else would it mean? These seem like moral universals, as much as the complex numbers or the fundamental theorem of calculus are universal.

Daniel Fagella: I like that. When you say civilizations, you mean non-Earth civilizations as well?

Scott Aaronson: Yes, exactly. We’re theorizing with not nearly enough examples. We can’t see these other civilizations or simulated civilizations running inside of computers, although we might start to see such things within the next decade. We might start to do experiments in moral philosophy using whole communities of Large Language Models. Suppose we do that and find the same principles keep leading to flourishing societies, and the negation of those principles leads to failed societies. Then, we could empirically discover and maybe even justify by some argument why these are universal principles of morality.

Daniel Fagella: Here’s my supposition: a water droplet. I can’t make a water droplet the size of my house and expect it to behave the same because it behaves differently at different sizes. The same rules and modes don’t necessarily emerge when you scale up from what civilization means in hominid terms to planet-sized minds. Many of these outer-world civilizations would likely have moral systems that behoove their self-interest. If the self-interest was always aligned, what would that imply about the teachings of Confucius and Jesus? My firm supposition is that many of them would be so alien to us. If there’s just one organism, and what it values is whatever behooves its interest, and that is so alien to us…

Scott Aaronson: If there were only one conscious being, then yes, an enormous amount of morality as we know it would be rendered irrelevant. It’s not that it would be false; it just wouldn’t matter.

To go back to your analogy of the water droplet the size of a house, it’s true that it would behave very differently from a droplet the size of a fingernail. Yet today we know general laws of physics that apply to both, from fluid mechanics to atomic physics to, far enough down, quantum field theory. This is what progress in physics has looked like, coming up with more general theories that apply to a broader range of situations, including ones that no one has ever observed, or hadn’t observed at the time they came up with the theories. This is what moral progress looks like as well to me—it looks like coming up with moral principles that apply in a broader range of situations.

As I mentioned earlier, some of the moral principles that people were obsessed with seem completely irrelevant to us today, but others seem perfectly relevant. You can look at some of the moral debates in Plato and Socrates; they’re still discussed in philosophy seminars, and it’s not even obvious how much progress we’ve made.

Daniel Fagella: If we take a computer mind that’s the size of the moon, what I’m getting at is I suspect all of that’s gone. You suspect that maybe we do have the seeds of the Eternal already grasped in our mind.

Scott Aaronson: Look, I’m sorry that I keep coming back to this, but I think that the brain the size of the Moon, still agrees with us that 2 and 3 are prime numbers and that 4 is not.

Daniel Fagella: That may be true. It’s still using complex numbers, vectors, and matrices. But I don’t know if it bows when it meets you, if these are just basic parts of the conceptual architecture of what is right.

Scott Aaronson: It’s still using De Morgan’s Law and logic. It would not be that great of a stretch to me to say that it still has some concept of moral reciprocity.

Daniel Fagella: Possibly, it would be hard for us to grasp, but it might have notions of math that you couldn’t ever understand if you lived a billion lives. I would be so disappointed if it didn’t have that. It wouldn’t be a worthy successor.

Scott Aaronson: But that doesn’t mean that it would disagree with me about the things that I knew; it would just go much further than that.

Daniel Fagella: I’m with you…

Scott Aaronson: I think a lot of people got the wrong idea, from Thomas Kuhn for example, about what progress in science looks like. They think that each paradigm shift just completely overturns everything that came before, and that’s not how it’s happened at all. Each paradigm has to swallow all of the successes of the previous paradigm. Even though general relativity is a totally different account of the universe than Newtonian physics, it could never have been done without everything that came before it. Everything we knew in Newtonian gravity had to be derived as a limit in general relativity.

So, I could imagine this moon-sized computer having moral thoughts that would go well beyond us. Though it’s an interesting question: are there moral truths that are beyond us because they are incomprehensible to us, in the same way that there are scientific or mathematical truths that are incomprehensible to us? If acting morally requires understanding something like the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem, can you really be faulted for not acting morally? Maybe morality is just a different kind of thing.

Because this moon-sized computer is so far above us in what scientific thoughts it can have, therefore the subject matter of its moral concern might be wildly beyond ours. It’s worried about all these beings that could exist in the future in different parallel universes. And yet, you could say at the end, when it comes down to making a moral decision, the moral decision is going to look like, “Do I do the thing that is right for all of those beings, or do I do the thing that is wrong?”

Daniel Fagella: Or does it simply do what behooves a moon-sized brain?

Scott Aaronson: That will hurt them, right?

Daniel Fagella: What behooves a moon-sized brain? You and I, there are certain levels of animals we don’t consult.

Scott Aaronson: Of course, it might just act in its self-interest, but then, could we, despite being such mental nothings or idiots compared to it, could we judge it, as for example, many people who are far less brilliant than Werner Heisenberg would judge him for collaborating with the Nazis? They’d say, “Yes, he is much smarter than me, but he did something that is immoral.”

Daniel Fagella: We could judge it all we want, right? We’re talking about something that could eviscerate us.

Scott Aaronson: But even someone who never studied physics can perfectly well judge Heisenberg morally. In the same way, maybe I can judge that moon-sized computer for using its immense intelligence, which vastly exceeds mine, to do something selfish or something that is hurting the other moon-sized computers.

Daniel Fagella: Or hurting the little humans. Blessed would we be if it cared about our opinion. But I’m with you—we might still be able to judge. It might be so powerful that it would laugh at and crush me like a bug, but you’re saying you could still judge it.

Scott Aaronson: In the instant before it crushed me, I would judge it.

Daniel Fagella: Yeah, at least we’ve got that power—we can still judge the damn thing! I’ll move to consciousness in two seconds because I want to be mindful of time; I’ve read a bunch of your work and want to touch on some things. But on the moral side, I suspect that if all it did was extrapolate virtue ethics forward, it would come up with virtues that we probably couldn’t understand. If all it did was try to do utilitarian calculus better than us, it would do it in ways we couldn’t understand. And if it were AGI at all, it would come up with paradigms beyond both that I imagine we couldn’t grasp.

You’ve talked about the importance of extrapolating our values, at least on some tangible, detectable level, as crucial for a worthy successor. Would its self-awareness also be that crucial if the baton is to be handed to it, and this is the thing that’s going to populate the galaxy? Where do you rank consciousness, and what are your thoughts on that?

Scott Aaronson: If there is to be no consciousness in the future, there would seem to be very little for us to care about. Nick Bostrom, a decade ago, had this really striking phrase to describe it. Maybe there will be this wondrous AI future, but the AIs won’t be conscious. He said it would be like Disneyland with no children. Suppose we take AI out of it—suppose I tell you that all life on Earth is going to go extinct right now. Do you have any moral interest in what happens to the lifeless Earth after that? Would you say, “Well, I had some aesthetic appreciation for this particular mountain, and I’d like for that mountain to continue to be there?”

Maybe, but for the most part, it seems like if all the life is gone, then we don’t care. Likewise, if all the consciousness is gone, then who cares what’s happening? But of course, the whole problem is that there’s no test for what is conscious and what isn’t. No one knows how to point to some future AI and say with confidence whether it would be conscious or not.

Daniel Fagella: Yes, and we’ll get into the notion of measuring these things in a second. Before we wrap, I want to give you a chance—if there’s anything else you want to put on the table. You’ve been clear that these are ideas we’re just playing around with; none of them are firm opinions you hold.

Scott Aaronson: Sure. You keep wanting to say that AI might have paradigms that are incomprehensible to us. And I’ve been pushing back, saying maybe we’ve reached the ceiling of “Turing-universality” in some aspects of our understanding or our morality. We’ve discovered certain truths. But what I’d add is that if you were right, if the AIs have a morality that is incomprehensibly beyond ours—just as ours is beyond the sea slug’s—then at some point, I’d throw up my hands and say, “Well then, whatever comes, comes.” If you’re telling me that my morality is pitifully inadequate to judge which AI-dominated futures are better or worse, then I’d just throw up my hands and say, “Let’s enjoy life while we still have it.”

The whole exercise of trying to care about the far future and make it go well rather than poorly is premised on the assumption that there are some elements of our morality that translate into the far future. If not, we might as well just go…

Daniel Fagella: Well, I’ll just give you my take. Certainly, I’m not being a gadfly for its own purpose. By the way, I do think your “2+2=4” idea may have a ton of credence in the moral realm as well. I credit that 2+2=4, and your notion that this might carry over into basics of morality is actually not an idea I’m willing to throw out. I think it’s a very valid idea. All I can do is play around with ideas. I’m just taking swings out here. So, the moral grounding that I would maybe anchor to, assuming that it would have those things we couldn’t grasp—number one, I think we should think in the near term about what it bubbles up and what it bubbles through because that would have consequences for us and that matters. There could be a moral value to carrying the torch of life and expanding potentia.

Scott Aaronson: I do have children. Children are sort of like a direct stake that we place in what happens after we are gone. I do wish for them and their descendants to flourish. And as for how similar or how different they’ll be from me, having brains seems somehow more fundamental than them having fingernails. If we’re going to go through that list of traits, their consciousness seems more fundamental. Having armpits, fingers, these are things that would make it easier for us to recognize other beings as our kin. But it seems like we’ve already reached the point in our moral evolution where the idea is comprehensible to us that anything with a brain, anything that we can have a conversation with, might be deserving of moral consideration.

Daniel Fagella: Absolutely. I think the supposition I’m making here is that potential will keep blooming into things beyond consciousness, into modes of communication and modes of interacting with nature for which we have no reference. This is a supposition and it could be wrong.

Scott Aaronson: I would agree that I can’t rule that out. Once it becomes so cosmic, once it becomes sufficiently far out and far beyond anything that I have any concrete handle on, then I also lose my interest in how it turns out! I say, well then, this sort of cloud of possibilities or whatever of soul stuff that communicates beyond any notion of communication that I have, do I have preferences over the better post-human clouds versus the worse post-human clouds? If I can’t understand anything about these clouds, then I guess I can’t really have preferences. I can only have preferences to the extent that I can understand.

Daniel Fagella: I think it could be seen as a morally digestible perspective to say my great wish is that the flame doesn’t go out. But it is just one perspective. Switching questions here, you brought up consciousness as crucial, obviously notoriously tough to track. How would you be able to have your feelers out there to say if this thing is going to be a worthy successor or not? Is this thing going to carry any of our values? Is it going to be awake, aware in a meaningful way, or is it going to populate the galaxy in a Disney World without children sort of sense? What are the things you think could or should be done to figure out if we’re on the right path here?

Scott Aaronson: Well, it’s not clear whether we should be developing AI in a way where it becomes a successor to us. That itself is a question, or maybe even if that ought to be done at some point in the future, it shouldn’t be done now because we are not ready yet.

Daniel Fagella: Do you have an idea of when ‘ready’ would be? This is very germane to this conversation.

Scott Aaronson: It’s almost like asking a young person when are you ready to be a parent, when are you ready to bring life into the world. When are we ready to bring a new form of consciousness into existence? The thing about becoming a parent is that you never feel like you’re ready, and yet at some point it happens anyway.

Daniel Fagella: That’s a good analogy.

Scott Aaronson: What the AI safety experts, like the Eliezer Yudkowsky camp, would say is that until we understand how to align AI reliably with a given set of values, we are not ready to be parents in this sense.

Daniel Fagella: And that we have to spend a lot more time doing alignment research.

Scott Aaronson: Of course, it’s one thing to have that position, it’s another thing to actually be able to cause AI to slow down, which there’s not been a lot of success in doing. In terms of looking at the AIs that exist, maybe I should start by saying that when I first saw GPT, which would have been GPT-3 a few years ago, this was before ChatGPT, it was clear to me that this is maybe the biggest scientific surprise of my lifetime. You can just train a neural net on the text on the internet, and once you’re at a big enough scale, it actually works. You can have a conversation with it. It can write code for you. This is absolutely astounding.

And it has colored a lot of the philosophical discussion that has happened in the few years since. Alignment of current AIs has been easier than many people expected it would be. You can literally just tell your AI, in a meta prompt, don’t act racist or don’t cooperate with requests to build bombs. You can give it instructions, almost like Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics. And besides giving explicit commands, the other thing we’ve learned that you can do is just reinforcement learning. You show the AI a bunch of examples of the kind of behavior we want to see more of and the kind that we want to see less of. This is what allowed ChatGPT to be released as a consumer product at all. If you don’t do this reinforcement learning, you get a really weird model. But with reinforcement learning, you can instill what looks a lot like drives or desires. You can actually shape these things, and so far it works way better than I would have expected.

And one possibility is that this just continues to be the case forever. We were all worried over nothing, and AI alignment is just an easier problem than anyone thought. Now, of course, the alignment people will absolutely not agree. They argue we are being lulled into false complacency because, as soon as the AI is smart enough to do real damage, it will also be smart enough to tell us whatever we want to hear while secretly pursuing its own goals.

But you see how what has happened empirically in the last few years has very much shaped the debate. As for what could affect my views in the future, there’s one experiment I really want to see. Many people have talked about it, not just me, but none of the AI companies have seen fit to invest the resources it would take. The experiment would be to scrub all the training data of mentions of consciousness—

Daniel Fagella: The Ilya deal?

Scott Aaronson: Yeah, exactly, Ilya Sutskever has talked about this, others have as well. Train it on all other stuff and then try to engage the resulting language model in a conversation about consciousness and self-awareness. You would see how well it understands those concepts. There are other related experiments I’d like to see, like training a language model only on texts up to the year 1950 and then talking to it about everything that has happened since. A practical problem is that we just don’t have nearly enough text from those times, it may have to wait until we can build really good language models with a lot less training data right, but there there are so many experiments that you could do that seem like they’re almost philosophically relevant, they’re morally relevant.

Daniel Fagella: Well, and I want to touch on this before we wrap because I don’t want to wrap up without your final touch on this idea of what folks in governance and innovation should be thinking about. You’re not in the “it’s definitely conscious already” camp or in the “it’s just a stupid parrot forever and none of this stuff matters” camp. You’re advocating for experimentation to see where the edges are here. And we’ve got to really not play around like we know what’s going on exactly. I think that’s a great position. As we close out, what do you hope innovators and regulators do to move us forward in a way that would lead to something that could be a worthy successor, an extension and eventually a grand extension of what we are in a good way? What would you encourage those innovators and regulators to do? One seems to be these experiments around maybe consciousness and values in some way, shape, or form. But what else would you put on the table as notes for listeners?

Scott Aaronson: I do think that we ought to approach this with humility and caution, which is not to say don’t do it, but have some respect for the enormity of what is being created. I am not in the camp that says a company should just be able to go full speed ahead with no guardrails of any kind. Anything that is this enormous—it could be easily more enormous than, let’s say, the invention of nuclear weapons—and anything on that scale, of course governments are going to get involved. We’ve already seen it happen starting in 2022 with the release of ChatGPT.

The explicit position of the three leading AI companies—OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic—has been that there should be regulation and they welcome it. When it gets down to the details of what that regulation says, they might have their own interests that are not identical to the wider interest of society. But I think these are absolutely conversations that the world ought to be having right now. I don’t write it off as silly, and I really hate when people get into these ideological camps where you say you’re not allowed to talk about the long-term risks of AI getting superintelligent because that might detract attention from the near-term risks, or conversely, you’re not allowed to talk about the near-term stuff because it’s trivial. It really is a continuum, and ultimately, this is a phase change in the basic conditions of human existence. It’s very hard to see how it isn’t. We have to make progress, and the only way to make progress is by looking at what is in front of us, looking at the moral decisions that people actually face right now.

Daniel Fagella: That’s a case of viewing it as all one big package. So, should we be putting a regulatory infrastructure in place right now or is it premature?

Scott Aaronson: If we try to write all the regulations right now, will we just lock in ideas that might be obsolete a few years from now? That’s a hard question, but I can’t see any way around the conclusion that we will eventually need a regulatory infrastructure for dealing with all of these things.

Daniel Fagella: Got it. Good to see where you land on that. I think that’s a strong, middle-of-the-road position. My whole hope with this series has been to get people to open up their thoughts and not be in those camps you talked about. You exemplify that with every answer, and that’s just what I hoped to get out of this episode. Thank you, Scott.

Scott Aaronson: Of course, thank you, Daniel.

Daniel Fagella: That’s all for this episode. A big thank you to everyone for tuning in.

Follow

Follow