Einstein the man

Sorry for the inordinate delay in updating! This weekend I was busy with several things, one of which was “EinsteinFest,” Perimeter Institute’s celebration of the hundred-year anniversary of Einstein’s annus mirabilis. The Fest is a monthlong program of exhibits, talks, etc., aimed at the general public, and covering four topics: “The Science, The Times, The Man, The Legacy.” This weekend’s talks were about “The Man,” which is why I attended.

See, I was worried that the Fest would place too much emphasis on Einstein the sockless symbol of scientific progress, Einstein the secular saint, Einstein the posthumous salesman for Perimeter Institute. And how it could do that without indulging in the very pomposity that Einstein himself detested?

My fears were not assuaged by the many exhibits devoted to Freud, Picasso, the Wright Brothers, the automobile, fashion at the turn of the century, and so on. These exhibits gave visitors the impression of a great band of innovators marching into the future, with Einstein cheerfully in front. The reality, of course, is that Einstein never marched in anyone’s band, and — like his friend Gödel — saw himself as opposed to the main intellectual currents of the time.

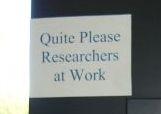

It didn’t help either that, to handle the influx of visitors, Perimeter has basically transformed itself into Relativistic Disney World — complete with tickets, long lines, guides wearing uniforms, signs directing traffic, cordoned-off areas, and an outdoor tent for kids called “Physica Fantastica.” To some extent I guess this was unavoidable, although sometimes it resulted in unintended comedy:

(Sorry, I just bought a digital camera and couldn’t resist.)

So it was a pleasure to attend the talks on “Einstein the Man” and find that, in spite of everything, they were fantastic. We heard David Rowe on Einstein and politics, Trevor Lipscombe on Einstein and Mileva, and John Dawson on Einstein and Gödel. Partly these speakers won me over with wisecracks (Dawson: “Gödel thought he’d found a flaw in the Constitution, by which the US could legally turn into a dictatorship. In light of recent events, I don’t see why anyone would doubt him”). But mostly they just let the old man speak for himself. We saw Einstein write the following to his then-mistress Elsa:

If you were to recite the most beautiful poem ever so divinely, the joy I would derive from it would not come close to the joy I experienced when I received the mushrooms and goose cracklings you cooked.

And to Mileva, during the months when he was finishing general relativity:

You will see to it: (1) that my clothes and linen are kept in order; (2) that I am served three regular meals a day in my room; (3) that my bedroom and study are always kept in good order and that my desk is not touched by anyone other than me.

We saw Einstein the pacifist urging the Allies to rearm at once against Hitler, and Einstein the secular internationalist supporting the creation of Israel. And eventually we came to understand that this was not an oracle spouting wisdom from God; it was just a guy with a great deal of common sense — as much common sense as anyone’s ever had. Isn’t it strange that, despite deserving to be celebrated, he is?

Follow

Follow

Comment #1 October 17th, 2005 at 9:30 am

Biographical history can be a fascinating thing (when properly done). I’m glad to hear that the presenters really did speak about “Einstein, The Man” and not “Einstein, the God.” So many histories fail to recognize that major historical figures were people like everyone else… and that their whole story needs to be told.

Comment #2 October 17th, 2005 at 12:49 pm

I grew up listening to stories about my grandfather meeting Einstein when he was at Caltech and a legend that my great grandmother accompanied him when he played the violin while he was at Caltech. My grandfather describes how he was walking across the campus at Caltech when he saw Einstein just sitting on a chair which he’d taken from inside. He was just leaning back and enjoying the sun. Maybe he was thinking….maybe he was just enjoying the sun. I wish all scientists were that laid back!

Comment #3 October 17th, 2005 at 12:50 pm

I completely agree that Einstein was a very human figure who was blessed with an uncommon amount of common sense. Indeed, in his great early period he was only seeing things that were staring the entire physics establishment in the face. But the establishment was insensibly stubborn in that period. Only Einstein’s late success, general relativity, goes well beyond what other people should have noticed.

I think that the establishment has much more common sense than it did 100 years ago and it may not be possible for anyone now to have an Einstein year like 1905.

It should also be recognized that Einstein’s common sense was not evenly distributed. Despite singing praises to Elsa, both of his marriages went bad. His letter to Mileva quoted here is just awful. In fact everything that Einstein did — physics, politics, romance — was a mix of sweet poetry and sour stubbornness.

It is possible that Mileva Einstien can also be blamed for what went wrong in their marriage. Somehow it seems like Albert Einstein could have better handled whatever happened in that family, with one exception. Their younger son developed schizophrenia, which is not something that any family can cope with well.

Arguably Neils Bohr had as much common sense as Einstein, but more evenly distributed. Bohr had a great marriage and he didn’t refuse to believe quantum mechanics. People whose wisdom is evenly distributed may be less famous in the end.

Comment #4 October 17th, 2005 at 1:50 pm

“People whose wisdom is evenly distributed may be less famous in the end.”

That’s a wonderful insight, Greg, which raises the obvious question: is it wiser to be unevenly wise?

Comment #5 October 17th, 2005 at 2:45 pm

If fame is what you want. But is there anything wise about being famous? I don’t see it. A taste of fame is nice, but beyond that I would rather be influential than famous.

One interesting example here is Ed Witten. In my opinion, he is and will be about as influential as Einstein. It is true that the establishment is more adept than in Einsten’s day, but it is also better at merit selection, and Witten is certainly an amazing standout. Unlike Einstein, Witten is working hard not to become too famous, although it may be impossible problem. Witten seems like a very wise person as well as a brilliant physicist and mathematician.

Another interesting example, almost contemporary to Einstein, was John von Nuemann. I don’t think that he actively avoided fame. Nonetheless he was profoundly influential in several ways just below the radar screen.